- 5.1 Introduction

- 5.2 Strengthen and reform the multilateral trading system

- 5.3 Enhance support measures for LDCs and graduates

- 5.4 Utilise new trading opportunities post-Brexit

- 5.5 Revive the tourism and travel sector, especially for small states

- 5.6 Leverage digital technologies for trade, development and competitiveness

- 5.7 Develop effective frameworks for governing digital trade

- 5.8 Develop a newly invigorated Aid for Digital Trade initiative

- 5.9 Digitise trade facilitation and strive for paperless trade

- 5.10 Promote sustainable trade and enable a more circular economy

- 5.11 Conclusion and way forward

Chapter 5:Pathways to Post-COVID Trade Recovery and Resilience Building

Trade can offer positive solutions to manage the COVID-19 pandemic, support economic recovery and spur the transition towards more inclusive and sustainable economies. The Commonwealth's diverse members will face varied opportunities and challenges and follow multiple recovery tracks based on the structure of their economies, the composition of their exports and their inherent features and vulnerabilities. Commonwealth countries can look to use their global and intra-Commonwealth trade as essential tools for building back better and promoting a more inclusive, resilient and sustainable future.

Chapter 5 identifies and examines 10 inter-related policy areas for revitalising trade. Some of the key takeaways are:

- Global economic prospects over the next few years will determine trade recovery, although strengthened multilateral and regional co-operation will enable and enhance developing countries' participation in world trade, especially least developed countries and graduates.

- The UK's new trade agreements with Commonwealth countries offer untapped opportunities to expand trade and investment and deepen economic co-operation, including in services, digital trade and FinTech.

- Tourism-dependent countries need to implement recovery plans that address demand and supply factors, support domestic and regional travel, and make the industry more resilient, including by adopting digital technologies.

- Commonwealth countries can harness digital technologies to boost their trade recovery and improve competitiveness, adopt paperless trade, and promote more sustainable and circular trade, especially for agriculture and fisheries.

- Recovery efforts should be framed overall by the importance of ensuring inclusive trade for women and youth and especially promoting women's economic empowerment.

5.1 Introduction

Trade can offer positive solutions to manage the COVID-19 pandemic and will be an essential tool for economic recovery. With vaccines being distributed globally, many countries are starting to lift national restrictions, open economies and resume trade and travel. Each Commonwealth member country has its own unique pathway and policy options for recovery, although access to vaccines plays an indispensable part for all of them. Digital technologies can enable this economic recovery process, while vaccination programmes are likely to fare better in countries where supply chains and public health services are digitised. Overall, the outlook for Commonwealth countries' trade recovery is inextricably linked to global economic prospects (IMF, 2021b) as well as the structure of their economy, the composition of their exports and their inherent characteristics and vulnerabilities, especially for least developed countries (LDCs) and small states. Commonwealth countries can also leverage regional trade agreements and regional co-operation mechanisms, discussed in the previous chapter, to grow their exports and build back better from the pandemic.

This chapter sets out some of the possible pathways for trade recovery from the pandemic. It identifies and examines 10 inter-related policy areas for revitalising trade, while ensuring inclusiveness, especially for women and youth, and promoting more sustainable trade and circular economy principles.

5.2 Strengthen and reform the multilateral trading system

An effective rules-based global trading system offers the best framework to enable an inclusive and sustainable recovery in world trade. This requires members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) to work collectively to strengthen and reform trade multilateralism to tackle this century's new and emerging trade issues and challenges (Soobramanien et al., 2019). However, the certainty and stability of the rules-based multilateral trading system is increasingly at risk from the geopolitical and geo-economic rivalry between the USA and China, the growing backlash against globalisation in many countries and the use of unilateral trade measures by some WTO members. More recently, complaints by the USA of "overreach" by the WTO's Appellate Body (AB), leading to its refusal to agree to new appointments as the terms of appointees expired, thereby rendering the AB dysfunctional (Remy, 2020), and China's attempts to advantage state-owned enterprises have aggravated existing tensions. There are also concerns that some parts of the WTO rulebook for managing world trade may be out-dated. These rules need to take into consideration the growth of trade in digital goods and services, changing modes of manufacturing and the challenges of climate change, natural disasters, environmental sustainability and biodiversity loss.

With a new WTO Director-General at the helm, the need to undertake some reform and strengthen the WTO system is widely recognised. For this purpose, there are various proposals by WTO members and groups, for example the Canada-led Ottawa Group and the Africa Group. In October 2019, Commonwealth Trade Ministers reaffirmed their commitment to work constructively together and with other WTO members on the necessary reform of the organisation and urged that any reform in the WTO take into account the views of all members.

It could be useful to situate these discussions on reforming the WTO in the context of its founding purpose. The Preamble to the Marrakesh Agreement highlights the WTO's objectives as increasing incomes, helping create employment, supporting sustainable development and raising living standards (WTO, 1995). Moreover, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development recognises the role of international trade - both directly and through its indirect influences in other areas - in achieving many specific Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and targets. For example, trade directly appears under seven goals concerning hunger, health and well-being, employment, infrastructure, inequality, conservative use of oceans and strengthening partnerships (UN, 2015). Bearing this in mind, the WTO should strive to respond to the needs of its more disadvantaged members by ensuring a level playing field in world trade and providing a platform for them to articulate and advance their trade and development-related interests. WTO members could consider several immediate and prospective actions to build a more robust rules-based trading system.

5.2.1 Immediate actions

In the short term, consideration could be given to avoiding protectionism and improving vaccine production and distribution, strengthening the enabling environment for e-commerce, addressing fisheries subsidies and improving food security.

One of the WTO's key functions is promoting transparency and predictability in world trade by requiring members to notify their domestic measures affecting trade and submitting their trade policies for regular review. To enhance certainty in times of crisis, WTO members should work to strengthen disciplines on export restrictions. They can also improve the functioning of the regular working bodies to monitor trade policy responses to the pandemic, especially vaccine distribution, and ensure any measures are "temporary, targeted, proportional and transparent" (WTO, 2020l). The WTO membership should also strive to reconcile intellectual property rules and public health to help ensure affordable and equitable access to vaccines to help revitalise global trade, the movement of goods and people and the opening of economies. Easing domestic regulations to ensure a ready supply of service providers in essential sectors like health care could also facilitate post-pandemic preparation (Kampel and Anuradha, 2021).

COVID-19 has underscored the importance of digital trade, especially e-commerce and the online delivery of certain services, for mitigating some of the consequences of the pandemic, as discussed in Chapter 2. With this in mind, WTO members should consider ways to accelerate e-commerce discussions in an inclusive manner to support the development of this digital trade sector. They could start by identifying any areas where convergence is possible. As these discussions progress, and given the digital divide between WTO members, it is imperative to prioritise the development dimension to build digital trade capacity in developing countries and LDCs. It is also important to explore practical solutions to address many legitimate concerns of these countries, for example through a new and invigorated Aid for Digital Trade initiative (see Section 5.8) or drawing on the Trade Facilitation Agreement's innovative approach to implementation linked to capacity support.

A negotiated agreement on fisheries is long overdue and should be adopted at the 12th Ministerial Conference of the WTO (MC12).1 Fish stocks are being depleted at unsustainable rates, affecting economic growth, food security and livelihoods in many coastal countries and communities, especially small states and small island developing states (SIDS). WTO members are seeking comprehensive and practical disciplines to prohibit specific forms of fisheries subsidies that contribute to overcapacity and overfishing, while also eliminating subsidies that contribute to illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing, and considering effective and appropriate special and differential treatment for developing countries and LDCs. Since all major economies have an interest in the fisheries negotiations - and delivering the SDGs - there is a strong possibility of reaching an outcome.

The pandemic has also fuelled discussions on the need to maintain and enhance food security. In response to COVID-19, several producing countries adopted measures that restricted trade in food (see Chapter 4), while others resorted to stockholding to ensure sufficient domestic supplies. This jeopardised the security of food supplies for many developing countries and LDCs, which rely on global markets to meet their food and nutritional needs. Some WTO members have stressed the need to reach an outcome on a permanent solution to public stockholding (PSH) to help ensure food availability, especially for the poor and the most vulnerable, during times of crisis. However, other developed and developing country members are cautious that some of these programmes may cause trade distortions and that products benefiting from PSH should not be exported.

5.2.2 Prospective actions

As part of a broader reform agenda, it is paramount to find a solution to the dispute settlement impasse and to identify practical ways for trade multilateralism to support greater environmental sustainability, especially in light of the SDGs and global commitments to addressing the climate crisis.

An urgent priority is to ensure a functional Dispute Settlement Understanding (DSU) and AB, which is critical to preserve the rules-based multilateral trading system. As alluded earlier, on 10 December 2019, the AB was rendered dysfunctional, leaving the WTO without a credible enforcement mechanism and allowing losing parties to lodge appeals "into the void". Although WTO members have recourse to other dispute settlement alternatives, they are regarded as second best and some WTO members may not accept them. A sub-group of WTO members, including several Commonwealth countries, has proposed the Multiparty Interim Appeal Arbitration Agreement to imitate the defunct two-tier appeal process, although this does not enjoy widespread legitimacy (Remy, 2020).

A green recovery from the pandemic will require WTO members to consider urgent actions to address the increased risks and challenges of climate change, natural disasters, environmental sustainability and biodiversity loss. This requires the global community to pursue greater coherence and "mutual supportiveness" between the multilateral trade and environment regimes, especially regarding climate change, where the WTO has no specific provisions. This has manifested itself in a growing number of WTO disputes that involve energy, especially renewable energy (Rutherford, 2020). More recently, several countries, including Canada, EU members and the USA, have shown an interest in using border carbon adjustment mechanisms to tackle climate change (OECD, 2020e), which could be subject to WTO rules and procedures. These measures could also have significant implications for international trade and present smaller developing countries with a new set of challenges. They may also affect the investment landscape and require developing countries to design more integrated climate change investment plans.

There is an opportunity for the UK, which in 2021 chairs the G7 of industrialised nations and the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), to provide leadership and advocate globally for a greener trade-led recovery as well as additional support for the smallest and most vulnerable countries. Furthermore, it is salutary that 53 WTO members, including several Commonwealth countries, have indicated their willingness to start structured discussions on trade and environmental sustainability. These discussions seek to work on "deliverables" at MC12 and beyond on environmental sustainability in various areas of the WTO (WTO, 2020m). WTO members are considering advancing multilateral co-operation on trade in environmental goods and services as well as investment in green infrastructure, removing fossil fuel subsidies and investment in environmentally sustainable technologies. Plastics pollution and plastics trade that is environmentally sustainable are now also receiving much-needed attention. An informal dialogue, which involves several Commonwealth members, aims to start multilateral discussions on trade as a solution to the detrimental effects of plastic pollution on the environment, health and economy.

Efforts to strengthen and reform the multilateral trading system can underpin a broader framework for recovery. In particular, an enabling global trading environment will support and enhance the participation of developing countries, especially LDCs, in world trade, as discussed next.

5.3 Enhance support measures for LDCs and graduates

COVID-19 has significantly affected the trade prospects of the Commonwealth's LDC members and those graduating from this category. After Vanuatu's graduation in December 2020, Solomon Islands is set to follow in 2024. Bangladesh was also due to graduate in that year but its transition period has been extended by two years on the back of the pandemic (Centre for Policy Dialogue, 2021). For these and other Commonwealth LDCs, a protracted pandemic poses significant risks to sustainable graduation pathways.

LDC governments and their development partners will need to redouble efforts to tackle existing vulnerabilities and bridge the "resilience gap" if they are to effectively confront the heightened challenges emanating from COVID-19. Such factors should focus on developing productive capabilities in higher-productivity sectors and higher value-added activities to structurally transform their economies and make them more resilient to future shocks. Chapter 2 highlighted the digital divide that Commonwealth LDCs face. It is imperative to bridge this gap by enhancing digital literacy, promoting digital connectivity, investing in digital infrastructure and ensuring access to digital technologies.

Multilateral support can play a key role. The multilateral trading system must take into consideration the special requirements of LDCs (see Chapter 4). In turn, much can be done to enhance debt sustainability and to de-risk, incentivise and improve access to finance for LDCs to help provide the resources necessary to build back better in the wake of the pandemic. Progress in the next decade will be critical to ensure LDCs are not left behind. The end of the 10-year Istanbul Programme of Action (IPoA) in 2020 provides pause for critical reflection as well as an opportunity to develop a newly invigorated agenda of support for LDCs considering the heightened challenges resulting from COVID-19. The Fifth United Nations Conference on LDCs, which is scheduled for January 2022, will look to mobilise additional international support measures and actions for LDCs and foster a renewed partnership between LDCs and development partners (Gay, 2020). At the WTO, the LDC group of countries has also requested a comprehensive "smooth transition" process for graduating LDCs under the WTO system, enabling them to continue benefiting from some WTO flexibilities for a period of 12 years after graduating (WTO, 2020n).

Another area for support in terms of trade recovery for LDCs relates to building their capacity to take advantage of duty-free market access for a range of their exports in developed economies, including Australia, Canada, the EU, the UK and the USA, as well as some developing countries like China and India; the latter two countries will be key drivers of global recovery in 2021 (IMF, 2021b). Furthermore, developed countries can offer commercially meaningful preferences to LDCs to help them take advantage of the WTO services waiver to increase and diversify services exports. However, preference utilisation by many LDCs is low owing to their lack of productive capacity and trade-enabling infrastructure (Commonwealth Secretariat, 2015). LDCs can draw on the WTO's Enhanced Integrated Framework for LDCs, the United Nations Technology Bank for LDCs and other bilateral and regional Aid for Trade (AfT) programmes to strengthen their trading capacities, including for digital trade. This will be important to take advantage of existing and new trading opportunities in other countries, like the UK post-Brexit as well as to deepen the trade relationships with emerging economies, particularly China (Box 5.1).

Box 5.1 Commonwealth trade linkages with China beyond the pandemic

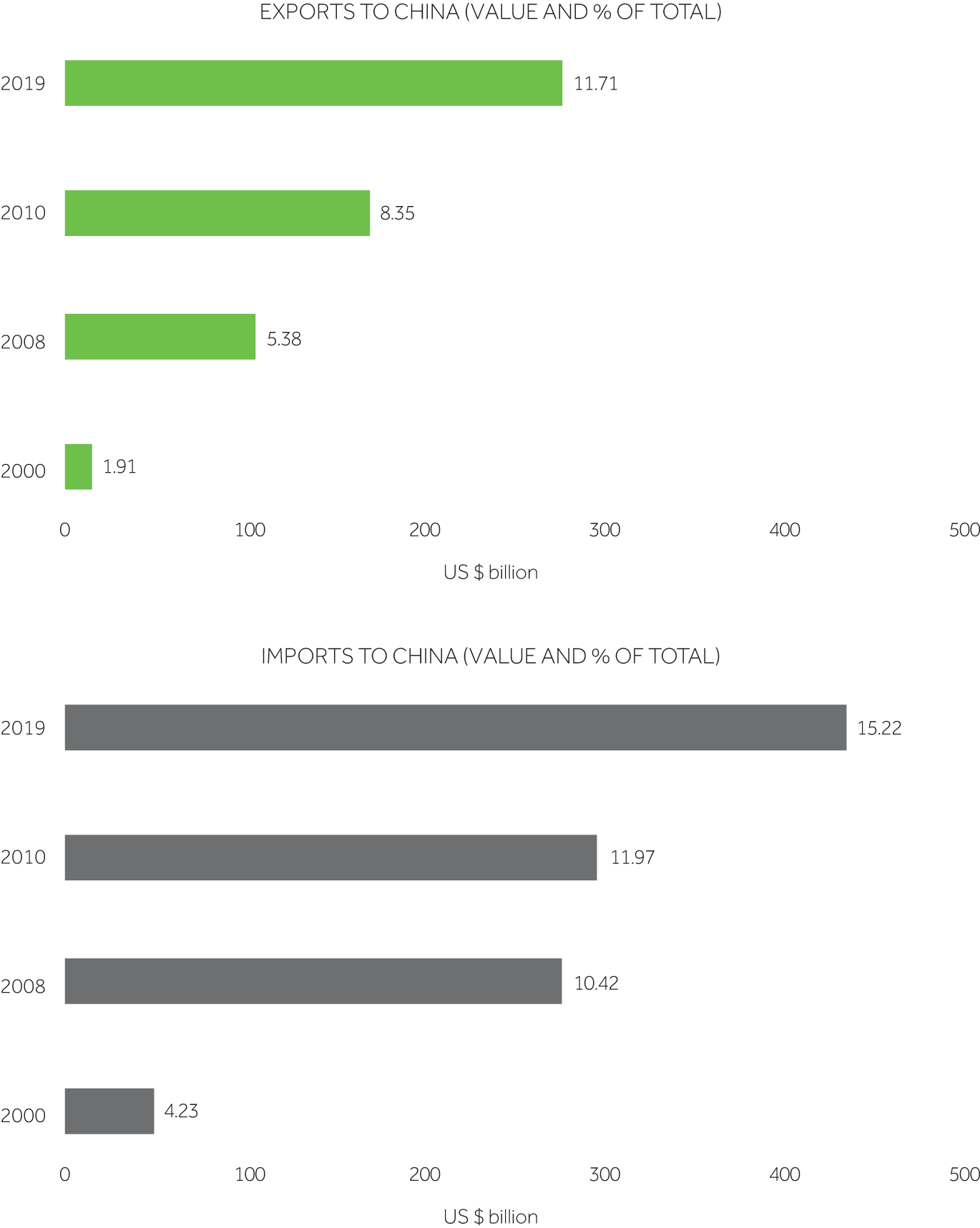

Commonwealth countries' trade linkages with China are strong and growing and have been resilient to the impacts of the COVID-19 crisis. Overall, China was the third-largest trading partner for Commonwealth countries (after the USA and the EU-28) in 2019, accounting for 12 per cent of the Commonwealth's exports and 15 per cent of imports. During the past two decades, the share of the Commonwealth's exports to China has risen six-fold, to 12 per cent in 2019, while the share of imports sourced from China has expanded four-fold, to 15 per cent (Figure 5.1). Given their geographical proximity, Asia-Pacific and South Asian Commonwealth countries are much more reliant on China for trade.

Figure 5.1 The Commonwealth's rising trade with China, 2000-2019

Note: The data illustrates the pattern of trade in goods. It covers exports to and imports from mainland China only and excludes Hong Kong. The numbers on the bar indicate trade share.

Note: The data illustrates the pattern of trade in goods. It covers exports to and imports from mainland China only and excludes Hong Kong. The numbers on the bar indicate trade share.Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using data from UNCTADstat dataset)

China is the only major economy to have registered positive growth in 2020, and its economy is projected to grow by 8.4 per cent in 2021. The spill-over effects of this growth offer numerous opportunities for Commonwealth countries to revive their trade flows. First, Commonwealth LDCs can benefit from duty-free access for a range of their exports. Second, China has ratified the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership three months ahead of schedule, indicating the significance it attaches to this trade agreement, which includes five Commonwealth countries. Third, China already has free trade agreements with several Commonwealth countries, and their focus should be on fully implementing these.2 Recently, the UK also expressed an interest in strengthening economic and trade links with China. For Africa, the year 2020 marked the 20th anniversary of the founding of the Forum on China-Africa Co-operation (FOCAC). The Beijing Action Plan 2019-2021 provides for considerable economic, industry, trade and investment co-operation, including establishing the China-Africa Private Sector Forum and a US$5 billion special fund to finance imports from Africa, as well as support to develop the continent's infrastructure, including through the Belt and Road Initiative (see Box 3.5 in Chapter 3).3 Finally, Commonwealth countries from Africa to the Caribbean could also benefit from pent-up demand for tourism once international travel resumes, especially since many Chinese travellers are affluent, with considerable spending potential. Spending by Chinese travellers makes up 21 per cent of all tourism spending worldwide. In addition, Chinese travellers spend on average more per trip than tourists from any other country (UNWTO, 2017).

5.4 Utilise new trading opportunities post-Brexit

The UK is a key destination for intra-Commonwealth exports, with considerable potential for further expansion beyond the pandemic. On 31 January 2020, the UK formally ceased to be a member of the EU and entered a transition period until December of that year. During this period, the existing rules on trade, travel and business between the UK and the EU continued to apply. Trade between the UK and the 27 members of the EU is now governed by the UK-EU Trade and Co-operation Agreement (TCA).4 The TCA, implemented on 1 January 2021, is a free trade agreement (FTA) covering all goods and limited services that leaves scope for regulatory regimes to diverge over time.5

5.4.1 UK-Commonwealth trading relations

In 2019, Commonwealth countries' exports to the UK were worth US$116 billion. The UK market absorbed around 13 per cent of intra-Commonwealth goods exports and 25 per cent of services exports. Dependence on the UK differs significantly among Commonwealth regions and member countries and by sectors (Figure 5.2). For example, many African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries rely heavily on the UK market for specific exports, including beef, bananas, fresh vegetables, fish, sugar, rum, textile and apparel products.

Figure 5.2 Share of Commonwealth merchandise and services exports to the UK, 2017-2019 average

Note: The shares represent the proportion of merchandise and services exports destined for the UK market during 2017-2019

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTADstat and WTO-OECD BaTIS datasets)

Collectively, the 19 sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries rely the most on the UK for both goods and services exports. Belize sends one-fifth of its total goods exports to the UK, while another eight countries send more than 5 per cent. More striking is the significance of the UK market for intra-Commonwealth services exports. Six countries trade more than 15 per cent of their total services with the UK. Another 12 send around 10-15 per cent. Overall, small states have the highest share for services (at around 16 per cent), which comes for the main part through the travel and tourism sector.

Although the UK accounts for only a small share of most Commonwealth LDCs' exports, its share is as high as 9 per cent for Bangladesh (mostly apparel products), almost 4 per cent for Malawi and over 2 per cent for Rwanda and Tanzania. On average, 6 per cent of LDC services exports are destined for the UK.

The UK's trade regimes and Commonwealth imports

The UK-EU TCA provides greater clarity for Commonwealth governments and business on how their trade might be affected both immediately and in the future. There may also be opportunities to deepen and enhance their broader economic relationship with the UK.

The UK's trade regimes are directly modelled on those of the EU (Table 5.2). Most countries with which the EU has an economic partnership agreement (EPA) or a FTA are covered by a UK FTA or Bridging Mechanism. For the rest, the UK has established a Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP), which, like its EU counterpart, has three segments that offer better market access terms than the WTO. These are the LDC Framework GSP, which offers market access equivalent to the EU's Everything But Arms (EBA), the Enhanced GSP regime, modelled on the EU's GSP+ and the General Framework GSP for other low- and lower-middle-income countries. Like its EU model, the UK GSP (except the LDC Framework) excludes many goods, especially agricultural products.6 Countries deemed to be too competitive for certain products are also "graduated out" of the GSP for those products. For example, India is graduated out of the GSP for 2,652 tariff lines (Stevens, 2021).

The UK's new trade agreements with ACP countries continue to provide duty-free and quota-free (DFQF) market access for their exports. However, the UK's pursuit of future trade deals globally could create greater competition for ACP suppliers. Moreover, some ACP exporters that depend heavily on the UK market for certain sensitive products, including bananas and sugar (Box 5.2), have raised concerns about the implications of the UK's tariff regime for their trade.

Box 5.2 The UK sugar market: a sweet or sticky deal for the ACP?

Sugar is a major export for several Commonwealth developing countries. For example, sugar makes up just over 30 per cent of Belize's total merchandise exports, about 20 per cent for Eswatini, 10 per cent for Mauritius and 9 percent for Fiji (Table 5.1). The UK is a traditional market for these sugar-producing countries, especially for raw sugar, which is then refined by Tate and Lyle. Barbados sends all its raw sugar to the UK, Belize around 83 per cent and Fiji approximately 48 per cent. This is an extremely sensitive sector for these countries. It earns foreign exchange, creates jobs and sustains many livelihoods. In 2017, the EU, including the UK as a member, reformed its restricted, high-priced sugar market in line with world prices. This reduced the value of ACP sugar exports.7

Table 5.1 The significance of the UK sugar market to Commonwealth ACP countries, 2017-2019 average

| ACP sugar exports to the UK* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top ACP exporters to the UK, by value | Share of sugar in total merchandise exports (%) | Value of sugar exports to the UK (US$ million) | Share of total sugar exports to the UK (%) | Value of raw sugar exports to the UK (US$ million) | Share of raw sugar exports to the UK (%) | |

| All ACP countries | 0.75 | 164.3 | 8.86 | 128.6 | 11.43 | |

| Of which | ||||||

| 1 | Belize | 30.91 | 51.8 | 83.21 | 51.8 | 83.21 |

| 2 | South Africa | 0.43 | 29.0 | 7.60 | 18.2 | 8.35 |

| 3 | Fiji | 8.17 | 28.7 | 48.26 | 28.7 | 48.28 |

| 4 | Mauritius | 9.91 | 20.5 | 10.40 | 14.1 | 17.38 |

| 5 | Mozambique | 3.41 | 20.1 | 11.35 | 9.5 | 20.63 |

| 6 | Jamaica | 0.79 | 5.1 | 37.81 | 1.9 | 30.27 |

| 7 | Guyana | 0.36 | 4.7 | 33.89 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| 8 | Eswatini | 18.28 | 4.2 | 1.21 | 4.2 | 1.36 |

| 9 | Barbados | 0.07 | 0.2 | 78.28 | 0.1 | 100.00 |

| 10 | Zambia | 1.42 | 0.0 | 0.02 | 0.0 | 0.02 |

Note: * Sugar is classified as HS code 1701; raw sugar is calculated as HS 170113 and 170114.

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using WITS data)

The UK's trade agreements with ACP countries continue to provide duty-free and quota-free (DFQF) market access for sugar. From 1 January 2021, the UK also implemented an annual autonomous tariff rate quota (ATQ) of 260,000 metric tonnes of raw sugar at zero tariffs (ACP-LDC Sugar Industry Group, 2020; also DIT, 2020). This raises the competitive stakes in the UK market for ACP producers because of their higher production costs compared with other producers, such as Brazil, while some global producers are also subsidised (DIT, 2020).

The UK and the EU both grant DFQF access to the ACP. However, their bilateral TCA does not provide "diagonal cumulation" provisions for ACP countries, which could affect demand for raw sugar imports from the ACP. More than 70 per cent of sugar consumption in the UK and the EU is in the form of processed food and drink, with considerable trade in these products between the UK and the EU (EPA Monitoring, 2021c). Without diagonal cumulation, raw sugar imported from the ACP and refined locally will not be considered as UK-originating when contained in processed products traded between the UK and the EU. Since these products would not benefit from the preferential rules of origin, UK companies might consider using UK or EU beet sugar instead.

These developments will continue to present a challenging outlook for ACP sugar-exporting countries in maintaining sustainable sugar agriculture and agro-industry as part of their economic mix for recovery and building back better.8 It will significantly affect smallholder producers, mainly in rural areas, and create unemployment as well as having impacts on export earnings, retarding progress towards achievement of the SDGs.

Consideration should be given to finding ways of preserving the value of preferential market access to the UK sugar market for ACP sugar-producing countries. Simultaneously, these countries need to devise ways to reduce their costs and improve their efficiency, including through multilateral and bilateral AfT initiatives.

Table 5.2 Nature of the UK's import regime for Commonwealth countries, March 2021

| Regime | Commonwealth countries | Reliance on the UK market | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Value ($, million) | Share (%) | ||

| Full FTA (9) | Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Seychelles, Singapore, South Africa | 9,204 | 1.8 |

| Partial FTA (1) | Canada | 14,924 | 3.3 |

| Provisional FTA (13) | Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Fiji, Ghana, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Papua | ||

| New Guinea, Saint Lucia, St Kitts and Nevis | 769 | 2.2 | |

| Bridging Mechanism (6) | Cameroon, Kenya, St Vincent and the Grenadines, Trinidad and Tobago, Samoa, Solomon Islands | 580 | 3.1 |

| GSP: LDC Framework (11) | The Gambia, Malawi, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Uganda, Tanzania, Zambia, Bangladesh, Kiribati, Tuvalu, Vanuatu | 3,663 | 6.5 |

| GSP: Enhanced Framework (2) | Pakistan, Sri Lanka | 2,511 | 7.0 |

| GSP: General Framework (2) | Nigeria, India | 10,665 | 2.8 |

| TCA (UK-EU) (2) | Malta and Cyprus | 267 | 4.1 |

| Most-favoured nation (7) | Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Malaysia, Maldives, Nauru, New Zealand, Tonga | 13,810 | 2.5 |

Note: Data is for exports in 2019. The share indicates the proportion of members' global exports destined for the UK.

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat based on Stevens (2021)

Importantly, the UK has made some improvements to the EU regime and there may be scope for further reforms, including reviewing certain standards or adopting simple and less restrictive rules of origin. For example, a longstanding concern of many ACP exporters relates to the high standards and regulations required for access to the EU market. Many argue that some of these regulations are unnecessarily onerous, even protectionist (Vickers, 2018). For instance, citrus exports from South Africa have faced more stringent sanitary and phyto-sanitary (SPS) conditions as a result of citrus black spot, a harmless fungal disease. However, from 1 April 2021, imported citrus into Britain (not Northern Ireland) will no longer require a SPS certificate, while other fruits, such as guavas, kiwis and passion fruit, are also exempt. More broadly, the UK's narrower range of climatic conditions and production than the whole of the EU provides scope to relax onerous health checks on a wider set of Commonwealth exports without endangering either UK producers or consumers (Stevens, 2021).

It was also noted in the previous chapter that Caribbean service suppliers have not, so far, been able to take advantage of their EPA with the EU - the only EPA with ACP countries covering services - as they face barriers related to the mutual recognition of standards and difficulties in obtaining visas. The UK could seek to ease these constraints, especially given the large Caribbean diaspora in the UK.

While trade continuity has been assured for most Commonwealth countries, there are some challenges. An immediate hurdle relates to border disruptions affecting supply chains moving Commonwealth-originating goods and services across the UK-EU border (such as cut flowers or audio-visual products) (Stevens, 2021). In addition, agri-food exports from Commonwealth developing countries that undergo some form of repackaging and/or processing within the triangular supply chain prior to onward shipment will also be affected by rules of origin and face most-favoured nation tariffs (e.g. Fairtrade sugar, fully traceable sustainably certified palm oil, cocoa products, tuna and other fisheries products) (EPA Monitoring, 2021a).9

Border controls on transhipped goods will become increasingly onerous as the EU and the UK's standards diverge, as has already begun. Agricultural products, including plant and animal exports, will have to be certified under both UK and EU standards because the UK is diverging from EU practice. Similarly, there are no provisions for the cross-recognition of manufactured goods standards, so any goods sold in both the UK and the EU market will have to be certified separately in each jurisdiction (Stevens, 2021).

Prospects for UK-Commonwealth trade

There are numerous opportunities to deepen economic relations between the UK and the Commonwealth beyond the pandemic. The UK government's commitment to this goal as part of its "Global Britain" strategy is evident, for example in hosting the 2020 UK-Africa Investment Summit in London and appointing trade envoys for countries or regions like the Commonwealth Caribbean. The UK is also a strong advocate and leading donor of AfT to help developing countries and LDCs boost their regional and world trade. Meanwhile, the creation of the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office provides a springboard to integrate all of the UK's diplomacy and development efforts (HM Government, 2021). There are further initiatives or opportunities to boost intra-Commonwealth trade with the UK, as introduced below.

First, the UK government aims to complete bilateral FTAs covering 80 per cent of UK trade by 2022, which would probably include tariff-free trade with three Commonwealth members - Australia, Canada and New Zealand - as well as the EU, Japan and the USA. Furthermore, the UK plans to accede to the mega-regional Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), discussed in Chapter 4, which includes six Commonwealth members: Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Malaysia, New Zealand and Singapore. These new trade deals have implications for Commonwealth countries and may require adjustment support (Box 5.3). Other FTAs with Commonwealth member countries are also possible. Modelling a UK-India FTA, for example, suggests that trade could increase substantially (Banga, 2017).10

Second, and related to the above, the UK can diversify some of its food trade towards the Commonwealth. Annually, the UK imports food worth US$65 billion and around 70 per cent of this is sourced from the EU. FTAs with major agricultural producers such as Australia, Canada and New Zealand could offer substantial scope for an increase in Commonwealth trade (Stevens, 2021).

Third, there is an opportunity to develop new and deeper forms of economic co-operation across the Commonwealth. There are already examples like the Commonwealth Standards Network. The UK Government has also identified digital trade as one of the main sources of economic growth to recover from the pandemic. The digital sector accounted for around 7.6 per cent of the UK economy in 2019 and UK trade flows are increasingly digital: an estimated two-thirds of UK services exports and a half of UK services imports were digitally delivered in 2018 (Sands et al., 2021; see Chapter 2). There is the possibility for UK agreements with other Commonwealth countries around digital trade, such as the planned negotiations for a separate UK-Singapore Digital Economy Agreement (Ciofu, 2020).

Fourth, there is considerable scope for further co-operation in services, where the UK is already relatively open in trade terms but where regulatory requirements are complex. A renewed partnership in areas like financial services technology could help further develop mutually beneficial trade. The increasing servicification of several Commonwealth economies, coupled with greater digitalisation, also provides opportunities for increasing bilateral services trade. The UK could consider offering commercially meaningful preferences to LDCs in line with the WTO LDC services waiver (Primack, 2017).

Finally, the UK is an important driver of services exports for many tourism-dependent ACP countries. For example, UK arrivals are most important for Barbados; second most important for Saint Lucia; and third most important for St Kitts and Nevis (Commonwealth Secretariat, 2016). These countries should already engage in branding and marketing to benefit from pent-up demand and excess savings once international travel resumes. This is especially important given that UK travellers are reported to spend seven times more than the average tourist in the Caribbean (Global News Matters Caribbean Research, 2016). However, this requires setting in place demand and supply measures to benefit, as discussed next.

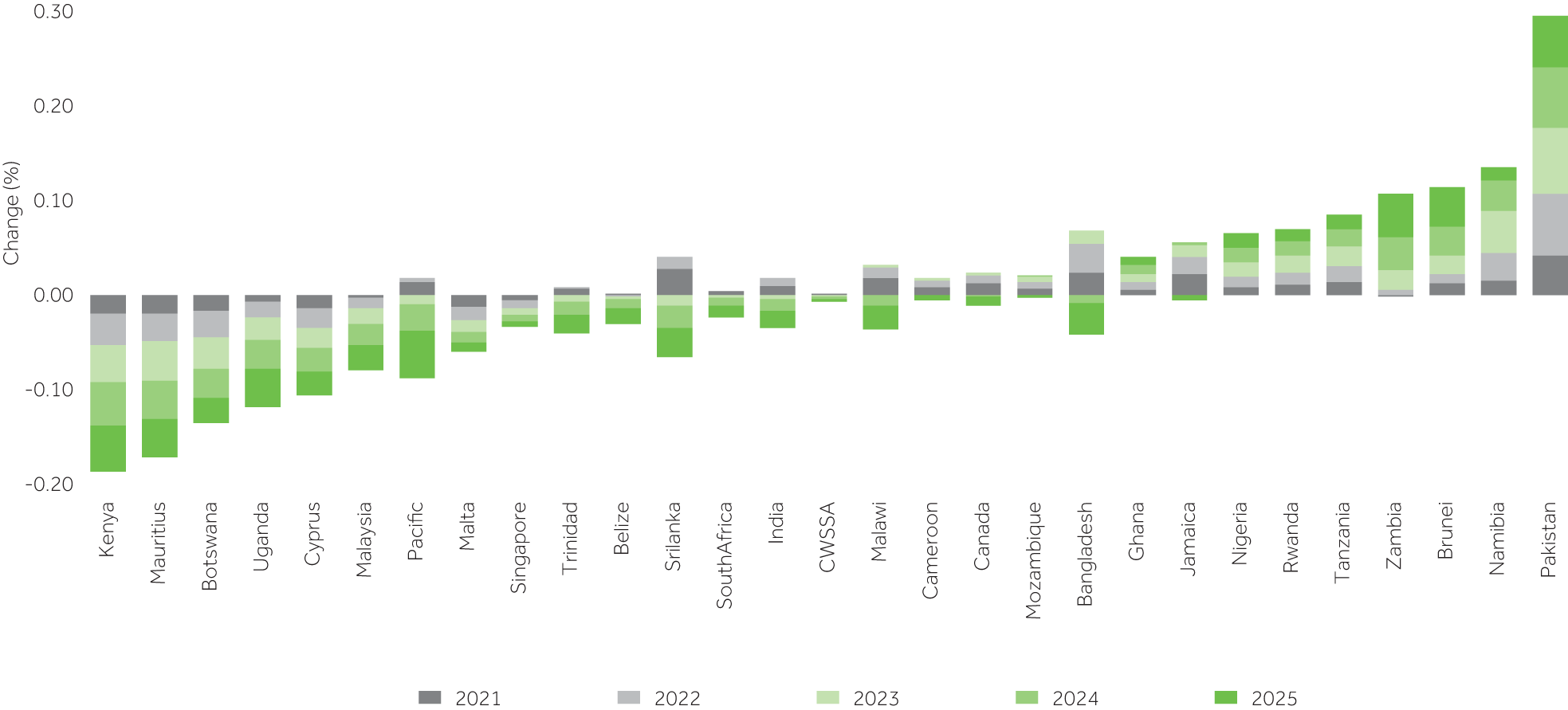

Box 5.3 Potential implications of future UK FTAs for Commonwealth countries

Dynamic Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP) modelling of tariff-free trade between the UK and Australia, Canada, the EU-27, Japan, New Zealand and the USA suggests these FTAs could affect many Commonwealth countries, although the effect is more pronounced for LDCs like Bangladesh, Lesotho, Malawi, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda (Annex 5.1).

The standard theory on the effects of any form of preferential trading agreement suggests they increase trade between members and reduce flows with third countries, leading to welfare effects for non-member countries (WTO, 2011). The UK's FTAs, like any other trading arrangements discussed in Chapter 4, could result in a loss of preferences for non-members and expose them to competition from more efficient suppliers. Overall, countries with high export dependence on the UK - for example Bangladesh (apparel), Botswana (beef), Belize (sugar) and Kenya (tea and vegetables) - could experience a modest decline in exports and overall trade. This is because competitors among the UK's FTA partners may displace their clothing, textiles and agricultural products and shrink their market share. There are some potential beneficiaries, like Brunei Darussalam, Malta, Nigeria, Pakistan and Zambia, which could gain marginally because their input costs are reduced as a result of the trade deals between the UK and its partners mentioned above. These trade adjustments would be gradual and could span around five years (Figure 5.3).

Figure 5.3 Potential short- and medium-term impacts on Commonwealth countries' exports, 2021-2025

Source: Gopalakrishnan (2021) for Commonwealth Secretariat

Source: Gopalakrishnan (2021) for Commonwealth Secretariat

Looking at overall sectors, the exports of meat, textiles, leather, processed food, rubber, plastics and vehicles from the USA, Japan, New Zealand and Australia would increase significantly, with a commensurate decline in the export of commodities under heavy manufacturing, textiles, processed food, meat, chemicals, and grains and crops from Commonwealth countries into the UK. Aside from the direct effects on exports, the modelling forecasts that countries reliant on the UK market for exports, such as Belize, Botswana, Kenya, Malaysia, Namibia, Sri Lanka and Trinidad and Tobago, may be affected through reductions to their gross domestic product (GDP), output, employment and investment, although the effects are relatively small and will diminish over time.

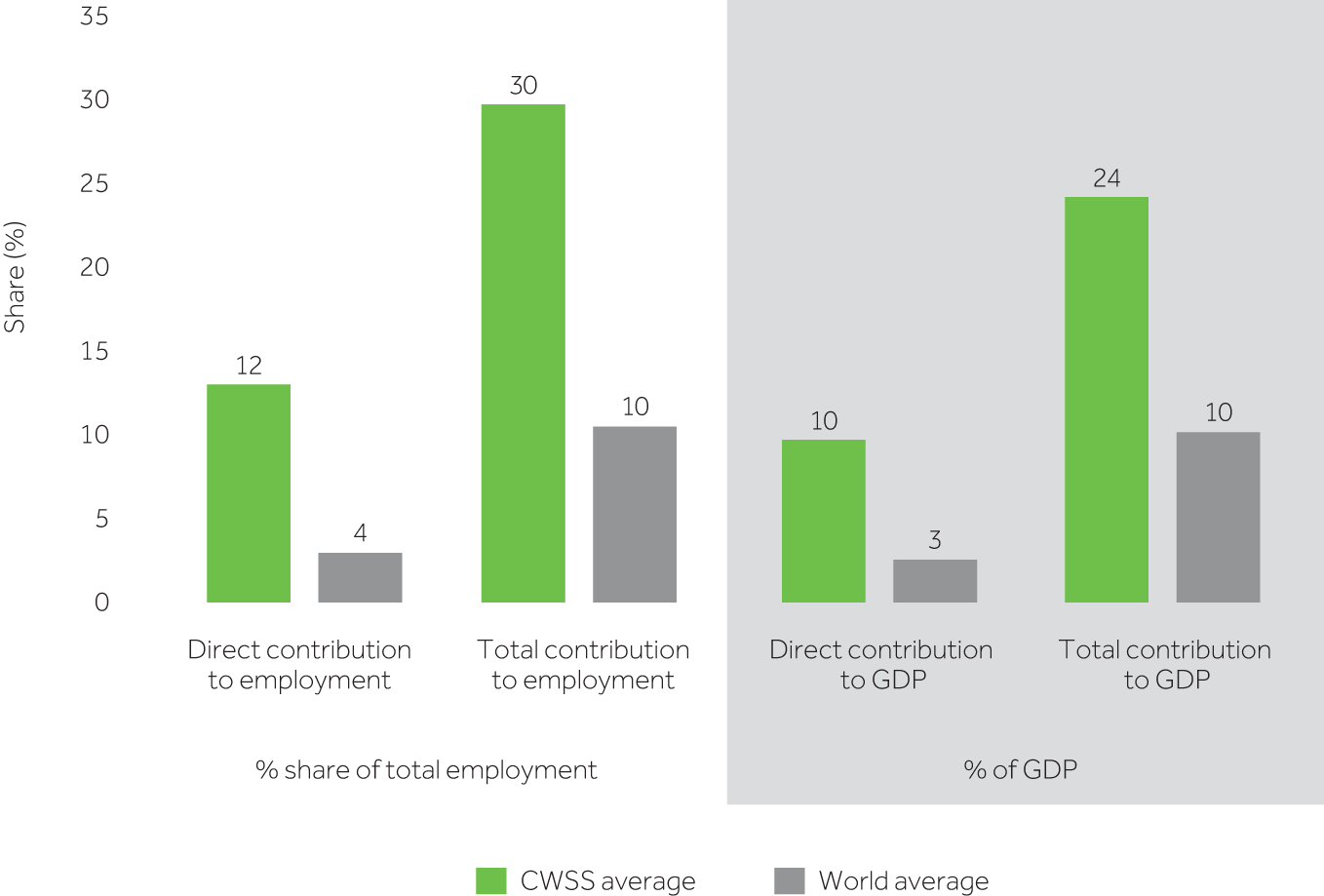

5.5 Revive the tourism and travel sector, especially for small states

The global tourism and travel sector has been the hardest hit by COVID-19, as Chapter 1 highlighted. Small states, particularly SIDS, have been the worst affected because they depend almost entirely on the tourism sector for revenue and employment opportunities, especially for women, youth, the informal sector and returning migrants. For 14 of the 32 Commonwealth small states, tourism contributes over 30 per cent of GDP. This share varies from as high as 56 per cent in Maldives and 43 per cent in Antigua and Barbuda and The Bahamas to 30 per cent in Barbados and Vanuatu (Figure 5.4).

Figure 5.4 Contribution of tourism to GDP and employment in Commonwealth small states, 2019

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using WTTC data)

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using WTTC data)

Many Commonwealth members have implemented response and recovery plans for the tourism sector based on industry body guidelines, with two broad categories of measures discernible: first, short-term, immediate crisis management responses that include stimulus and relief packages; and second, measures that focus on medium- to long-term recovery, especially to make the industry more resilient and adopting innovative technologies to facilitate operations. Though policy responses are highly specific to national contexts, and the duration of disruption to the tourism and travel industry is unknown, some useful lessons can be drawn from Commonwealth experiences, such as efforts to reopen the tourism industry in Maldives (see Box 5.4).

On the supply side, some countries have focused on maintaining existing supply capacity along the tourism value chain, which includes investing in and refurbishing critical infrastructure and capacity and skills development, in preparation for the reopening of tourism markets. Enhanced inter-sectoral national and regional collaboration has also improved supply-side readiness across regions and with the private sector. The pandemic has also created opportunities to integrate conservation, ecology, creative industries and cultural heritage offerings, with examples including chimpanzee rehabilitation in The Gambia, Liwonde National Park in Malawi, gorillas in Rwanda and Mount Yasur volcano in Vanuatu. Developing countries, especially LDCs, can in future also target AfT to promote and attract sustainable investment in their tourism sectors (Kampel, 2020b).

Box 5.4 Maldives leads the way in driving tourism recovery and a return to the "old normal"

When Maldives shut its borders in late March 2020, the impact was immediate and severe. The abrupt halt to international tourist arrivals struck to the heart of the economy, blighting the country's largest sector. To mitigate the damage and revive the economy, the Maldivian government adopted a sequenced approach to reopening the tourism sector. This capitalised on the advantage afforded by the country's geographically scattered islands, some of which are inhabited only by resort staff and tourists, allowing natural segregation from major towns and cities.

The reopening of the country's borders to international travellers in July 2020 was initially confined to those visiting resorts, hotels or liveaboard boats located on otherwise uninhabited islands. Thereafter, local tourism providers and guesthouses meeting stipulated health standards were permitted to reopen on 15 October 2020. To facilitate movement between islands, special permits were provided for guesthouses and hotels situated on locally inhabited islands to accommodate transiting passengers awaiting domestic transfers.

International tourists are obliged to present a negative PCR test for COVID-19 on arrival, which must have been taken within 96 hours of departure for Maldives. Incoming travellers are also required to complete an online health declaration form within 24 hours of departure. All travellers undergo thermal screening on arrival and those not exhibiting any symptoms are exempt from quarantine restrictions and free to begin their holiday.

Some resorts on private islands are offering PCR tests to guests upon arrival, who are then required to remain in their rooms or villas until the test results are received. Tourists testing positive for COVID-19 must go into isolation and receive compensation from the resort via a refund voucher (O'Ceallaigh, 2021). Those found to be free of COVID-19 can enjoy a normal, "mask-less", stay and move around the island as they wish.

These additional safety interventions have helped attract tourists by building confidence in the public health measures in place to prevent the spread of COVID-19. The Maldivian government introduced an app - TraceEkee - to facilitate detailed, community-driven contract tracing (Mohamed, 2020). To provide an additional layer of protection, the Ministry of Tourism has also launched a vaccination initiative to vaccinate tourism workers.

Governments have also implemented a variety of strategies to revitalise demand. These include nurturing the development of domestic staycations and intra-regional tourism; establishing cross-border travel corridors or "bubbles" between countries exhibiting low infection rates; offering flexible long-stay telework options to attract "digital nomads"; and conducting digital marketing and promotion strategies. Furthermore, the roll-out of comprehensive travel health and safety protocols as markets reopen and border restrictions ease has also garnered tourists' renewed trust and confidence in tourism destination markets (Kampel, 2020a).

The rapid acceleration of digitalisation and digital trade, as discussed in preceding chapters, has implications for the tourism sector too. Embracing digital and technological options will be a crucial component of a future tourism recovery strategy. For example, technology can be used to promote virtual tourism expos to scale up marketing, while e-commerce can create opportunities for local tourism suppliers accessing global customers. More advanced robotics and Artificial Intelligence (AI) can help streamline travel and accommodation booking and security processes at airports and at other border crossings. This will enable travel to be safer and more secure in the event of future epidemics and pandemics. Investing in augmented realities can also transport individuals to far-away escapes from their own homes, while paying for the experience at a fraction of the cost. Technology enabling digital versions of vaccine passports are already available or being developed, although not without controversy.11 Beyond tourism, there is considerable scope for Commonwealth countries to use information and communication technologies (ICTs) and more advanced frontier technologies to support recovery from the pandemic, as discussed next.

5.6 Leverage digital technologies for trade, development and competitiveness

Digitalisation and digital trade have helped some Commonwealth countries mitigate certain consequences of the pandemic, as observed in the previous chapters. While these technologies have accelerated globally, the reality is that many Commonwealth countries, especially LDCs, lag behind in digital engagement. Factors such as the quality of digital infrastructure and access to ICTs are increasingly driving international competitiveness and investment decisions, thus exerting a growing influence on economic performance and providing a means to support recovery from the pandemic. For these reasons, the highest consideration should be given to ensuring greater access, affordability and usage of ICTs.

For example, the internet economy has the potential to contribute close to US$180 billion to Africa's GDP by 2025, while improving productivity and efficiencies in various sectors, including agriculture, education, financial services, health care and supply chains (IFC and Google, 2020). Nine Commonwealth SSA countries could add around $100 billion to their combined GDP by 2025 if they intensively harness the internet.12 However, this requires extending mobile internet and integrating digital innovations beyond large urban cities, helping informal workers become more productive and empowering micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), especially women and youth entrepreneurs, for digital competition (AUC and OECD, 2021). Rwanda's digitally led development agenda offers much promise and provides an inspiring example of how digitalisation can connect and transform a country and overcome the constraints of being landlocked (Box 5.5).

Box 5.5 Rwanda embarks on digitally led development

Rwanda, a landlocked LDC, is spearheading an ambitious digital agenda and, in the process, emerging as a champion for digitally led development in Africa. Since 2000, four consecutive five-year strategies have targeted different elements of digital development, beginning with the establishment of enabling institutional, legal and regulatory frameworks, along with liberalisation of the telecommunications market, to lay the groundwork for an effective ICT sector. Subsequent strategies have looked to build ICT infrastructure, improve digital service delivery and accessibility, and develop digital skills, e-government services and cyber-security capabilities. Infrastructure development is key, with considerable progress in establishing a country-wide fibre optic network, and cross-border terrestrial links to undersea cables via Kenya and Tanzania have been crucial in improving internet capacity. This has helped achieve a 10-fold increase in access to international bandwidth since 2015 (World Bank, 2020c). Significant government investments in the 4G network, coupled with rapid adoption of mobile technologies, have further improved internet access. Estimates indicate that 4G services cover at least 95 per cent of the country.13 This is significantly higher than the regional average.

Developing digital skills are being prioritised through a series of innovative partnerships and initiatives. These provide training in coding, software development and programming skills aimed at both youth and working-age Rwandan women. More broadly, the government has embedded basic digital skills into national curricula at the primary and secondary levels (World Bank, 2020c).

There are many examples of innovative uses of digital technologies to advance economic and social development priorities in Rwanda. The government is at the forefront, embracing digitalisation to provide e-government services, including through IremboGov, a one-stop online portal for digital government services, while allowing payment using mobile money.14

Digital technologies are helping facilitate trade in Rwanda. Since its introduction in 2012, the Rwanda Electronic Single Window (RESW) has reduced customs clearance times and lowered both direct and indirect trade costs.15 These are crucial improvements, given the trade-related challenges Rwanda faces as a landlocked country. Most recently, the RESW has played a vital role in keeping trade flowing during the COVID-19 pandemic, helping avoid physical contact and enabling more officials and traders to work from home (Uwamariya et al., 2020). Another digital trade-facilitating measure, the Rwanda Trade Portal, provides an online platform to access step-by-step information on transit and import and export procedures.16

Aside from trade, some of the clearest examples of the power of digitalisation can be found in Rwanda's health care sector. Rwanda is on track to become the first country in the world with a digital-first universal primary care service, through a 10-year government collaboration with Babalyon Healthcare, a remote health care provider (Suarez, 2021).

Some initiatives in Rwanda's health care sector employ cutting-edge digital technologies. For example, a private company, Zipline, uses drones to deliver blood and other vital medical supplies to remote areas of Rwanda. This means local hospitals do not need expensive machinery to maintain supplies of refrigerated blood and other related products.

Countries can harness digital technology to support their economic recovery, depending on their levels of ICT adoption and digital engagement. In the short to medium term, digital trade, especially e-commerce and delivering some services online, can provide a pathway for mitigating several economic losses from COVID-19 and support the opening and resumption of many activities, although some online activity may decline with the roll-out of vaccines and treatments. In the longer term, growing digital trade, investing in digital capabilities, upskilling and training the workforce, and harnessing some of the frontier technologies linked to Industry 4.0 can help transform economies, build resilience to future shocks and better integrate sustainability into supply chains. This section sets out three areas - e-commerce, financial technology (FinTech) and frontier technologies - as potential tools to support trade recovery.

5.6.1 E-commerce

E-commerce, simply put, refers to digitally ordered, digitally delivered or digital platform-enabled transactions. The pandemic has accelerated growth of local and cross-border e-commerce, especially in developed countries. E-commerce in the USA is approaching a major milestone: in 2022, it will record its first trillion-dollar year (Adobe Analytics, 2020). However, as discussed in Chapter 2, readiness to engage in e-commerce is uneven within and between Commonwealth countries.

The experience of the pandemic provides a strong incentive for Commonwealth countries to invest in developing this digital trade sector for the domestic market as well as international trade. E-commerce marketplaces can potentially lower barriers to entry, reduce transaction costs, link informal and formal actors across sectors and geographies, and create new opportunities to access markets for MSMEs and women-owned businesses. Indeed, it is found that most of the benefits from digitalisation flow to traditional businesses, reinforcing the importance for "brick and mortar" companies of embracing digitalisation to improve competitiveness and build recovery and resilience (Ashton-Hart, 2020). Prior to the pandemic, the International Trade Centre (ITC) (in Al-Saleh, 2020) reported that four out of five small businesses involved in e-commerce were owned by women compared with just one of five businesses engaged in offline trade, suggesting e-commerce can serve as a key vehicle for women's economic empowerment.

E-commerce is also important for regional and international trade. It is especially beneficial for businesses and entrepreneurs in landlocked small states and SIDS in the Commonwealth because it can make it easier for them to reach customers in distant markets without incurring sunk costs to establish a presence in other markets or use intermediaries (Broome, 2016). There is also evidence to suggest e-commerce may support export diversification,17 thus potentially playing an important role in driving productivity growth through strengthened business-to-business and business-to-consumer connections, providing greater opportunities for buyers and sellers and supporting export diversification and economic transformation in developing countries, particularly LDCs. E-commerce will increase the demand for logistic supply chain services, thus creating jobs for information technology, postal and delivery services.

Leveraging e-commerce activity is thus likely to be important for post-COVID economic recovery. Doing so hinges on overcoming a range of existing barriers to e-commerce in some countries, including lack of appropriate regulatory frameworks and policies, cultural barriers to e-commerce adoption, low levels of digital skills, poor digital connectivity, the absence of suitable payment platforms and online dispute resolution, inefficient customs procedures, and costly and unreliable last-mile postage, transportation and logistics services (see Chapter 2).

5.6.2 Financial technology and innovation

Technology-enabled financial services (FinTech) evolved rapidly following the global financial crisis more than a decade ago (MacGregor, 2019). On the advanced side of FinTech there are virtual currencies, blockchains, digital wallets and tech start-ups providing a range of innovative financial services and solutions beyond traditional banking. However, mobile money and related lending and insurance services have arguably had the greatest transformational effect on lives and livelihoods in developing countries and LDCs by fostering financial inclusion, especially for women, and extending financial services to unbanked - especially rural - communities. This is especially important because the most frequently mentioned services sector in the SDGs is financial services (Nordås, 2021). The pandemic has underscored the importance of FinTech solutions for economies in lockdown. In many countries, mobile money solutions have made it possible to complete cashless transactions and have facilitated cross-border supply of services while maintaining social distancing.

Several Commonwealth member countries, both developed and developing, are global leaders, pioneers and innovators in the FinTech sector. Four members - the UK (2nd), Singapore (3rd), Australia (8th) and Canada (9th) - are ranked in the top 10 countries for FinTech on the 2020 Global Fintech Index City Rankings (Findexable, 2019). Two SSA countries, South Africa (37th) and Kenya (42nd), where M-Pesa has led the mobile money revolution, are ranked in the top 50, with Nigeria (52nd) a major player too.

Faced with the prospect of an increasingly digital future, Commonwealth countries need to develop and strengthen partnerships with the private sector, including young entrepreneurs and tech start-ups, to accelerate the provision of financial services in new and inclusive ways, including agritech and trade finance to help economic recovery. Commonwealth countries can consider "regulatory sandbox" approaches to experiment with innovative financial products or services, while pan-Commonwealth collaboration through "innovation hubs" could deliver great gains (Rutherford and Zaman, 2017). The Commonwealth Secretariat's FinTech Toolkit also provides a useful resource for countries to draw on as they look to build FinTech capabilities.

5.6.3 Frontier technologies

The rapid development and deployment of new "frontier technologies", sometimes called Industry 4.0, hold considerable promise and potential to help drive economic recovery and pursue the SDGs (UNCTAD, 2021b). However, there is also a risk that these technologies could leave most developing countries and LDCs behind, further widening the digital divide discussed in Chapter 2. UNCTAD (2021b) identifies 11 frontier technologies - namely, AI, the Internet of Things, big data, blockchain, 5G, 3D printing, robotics, drones, gene editing, nanotechnology and solar photovoltaic - which represent an estimated US$350 billion market, potentially growing to over $3.2 trillion by 2025.

The changing nature and composition of global trade and supply chains, and the implications for countries' comparative advantage, were highlighted in the previous chapter. For example, intensification and massification of 3D printing could by some estimates reduce world trade as much as 40 per cent by 2040 (ING, 2017). Many developing countries and LDCs have therefore raised legitimate concerns about the implications of automation, robotics and 3D printing for manufacturing capacity, labour markets and livelihoods.

Generally, technological progress could affect jobs in the Commonwealth and globally in at least three ways. First, it induces both increased and decreased demand for labour. There are small - and possibly positive - effects of enabling technologies on aggregate labour demand and employment, but also evidence of negative effects of replacing technologies, with costs often disproportionately borne by certain groups or communities in the forms of declining incomes or job losses, especially for low-skilled occupations that can be "automated" away (WTO, 2017). Second, it is positively correlated with labour productivity, meaning jobs that leverage digitisation generate more productivity, and these same jobs can readily be performed remotely, which has been essential as a result of the pandemic (Ashton-Hart, 2020). Third, its gains for developing countries - from jobs to trade - will be more pronounced the faster they catch up technologically. Bekkers et al. (2021) present evidence that technological change could boost developing countries' trade growth by 2.5 percentage points per annum by 2030, owing to falling trade costs and more intensive use of ICT services. The implications are unclear for more technologically constrained countries, especially LDCs, many of which still aspire to the traditional path to development of low-cost manufacturing exports to global markets.

Many Commonwealth members have made good progress harnessing some of these frontier technologies to develop their agriculture, energy, ocean and tourism sectors, among others (Commonwealth Secretariat, 2018a). However, most lack the digital infrastructure, capabilities and workforce skills to use, adopt and adapt frontier technologies, suggesting the need for significant investment in digitalisation. Overall, Commonwealth countries score lower than the global average on the new United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) Readiness for Frontier Technologies Index for 2019 (see Figure 5.5).18 Only two members, the UK (0.96) and Singapore (0.95), are ranked in the top five places on the Index, together with the USA (1.00), Switzerland (0.97) and Sweden (0.96). Asian Commonwealth members score the highest, on average, with Singapore, Malaysia, India and Brunei Darussalam above both the Commonwealth and the global averages. India over-performs relative to its GDP, largely because of its research and development (R&D) capabilities and abundance of skilled human resources (UNCTAD, 2021b).

Figure 5.5 Commonwealth countries' performance on the Readiness for Frontier Technologies Index, by country and region

Notes: Includes 41 Commonwealth countries based on data availability.

Notes: Includes 41 Commonwealth countries based on data availability.Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTAD data)

Two SSA members, South Africa and Mauritius, score higher than both the global and Commonwealth averages, and this corresponds with their relatively more developed ICT services sectors. Overall, the Caribbean SIDS score higher than Africa, with Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago and The Bahamas above the global and Commonwealth averages. The Index starkly highlights that this new technology revolution risks leaving behind LDCs. These countries need urgent investment to bridge their digital infrastructural gaps and support to develop forward-looking science, technology and innovation policy frameworks (UNCTAD, 2020d; see Chapter 2). For developing countries more broadly, the highest consideration should be given to the continued pursuit of structural economic transformation and better alignment of science, technology and innovation policies with industrial policies (UNCTAD, 2021b).

These frontier technologies and other ICTs are fuelled by the flow and transfer of data, both within and across national borders, and would require open digital markets to thrive (Elms, 2020). The next section examines some of the regulatory frameworks for digital trade at the national, regional and multilateral levels.

5.7 Develop effective frameworks for governing digital trade

While the digital economy, including digital trade, presents many opportunities for Commonwealth countries, as discussed above and in earlier chapters, this requires an appropriate and enabling regulatory system to operate, evolve and flourish. At the heart of the digital economy are the internet and data, which is stored and processed and flows across national borders. This requires a clear set of policies and regulations governing areas like data protection and privacy, data processing and localisation, cyber-security, e-transactions and digital signatures, and consumer protection (Banga and Raga, 2021). While Commonwealth developed countries have implemented most of these, many developing countries, especially SSA countries and small states, still lag in terms of legislative or regulatory progress in this area (Ashton-Hart, 2020).

Many Commonwealth countries are engaged in efforts to develop, co-operate, co-ordinate or harmonise rules and standards for digital trade through bilateral or regional trade deals and initiatives at the WTO. Around 60 per cent of all regional trade agreements (RTAs) concluded between 2010 and 2018 now contain digital trade provisions (Willemyns, 2020). The USA and China, together with the EU, have also developed different regulatory models in this area, given their large digital firms and interests (Gao, 2020). Of the recent mega-RTAs discussed in Chapter 4, the CPTPP and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership include digital trade chapters, albeit with different levels of ambition, while the African Continental Free Trade Area is scheduled to include a protocol on e-commerce in subsequent negotiations. This presents a unique opportunity for the Commonwealth's 19 SSA members and other African countries to develop common rules on e-commerce and harmonise digital economy regulations. The Digital Economy Partnership Agreement involving Commonwealth members New Zealand and Singapore is regarded by some as a model for next generation agreements in this area (Box 5.6).

There has been less progress on rule-making at the multilateral level, as noted earlier in this chapter. The WTO Work Programme on E-Commerce, established in 1998, allows for structured discussions on all trade-related issues linked to e-commerce and aspects concerning the moratorium on imposing customs duties on electronic transmissions.19 In December 2017, 71 WTO members announced a Joint Statement Initiative on trade-related aspects of e-commerce and subsequently launched plurilateral negotiations, which have been open to all WTO members. In December 2020, the now-86 participants agreed on a consolidated negotiating text addressing five broad issues: enabling e-commerce, openness, trust, telecommunications and market access, as well as cross-cutting issues (Nordås, 2021). They aspire to achieve a multilateral outcome around these issues at MC12. Many other WTO members are focusing their efforts on the existing WTO Work Programme and developing their domestic capacity for digital trade and tackling the digital divide.

The broader digital economy is anticipated to accelerate beyond the pandemic, bringing together a range of issues in cross-border settings, including digital trade, services, competition and taxation (customs duties on e-commerce and digital services taxes) (Elms, 2020; Sands et al., 2021). This will require greater regional and global coherence in rules and regulations for goods and services. The policy landscape for digital services, especially across borders, is rapidly evolving, with implications for negotiating commitments on trade in services under the WTO and other trade agreements (Anuradha, 2019; Nordås, 2021). For example, Chapter 1 examined switching of modes for delivering services during the pandemic owing to social distancing rules. However, digitalisation also enables services like road transport, construction and engineering, distribution and retail and possibly even tourism to be supplied abroad through Mode 1, which involves cross-border supply enabled through online or digital means. With these developments in mind, governments may consider ways of improving co-operation and co-ordination to reduce regulatory fragmentation, initially as part of deeper regional integration processes, discussed in the previous chapter. For example, regional online payments systems and harmonised rules for data and privacy can facilitate cross-border trade through e-commerce platforms. To strengthen developing countries' capacity for digital trade, the international community could consider allocating additional AfT specifically to the digital sector, as discussed next.

Box 5.6 The Digital Economy Partnership Agreement - a model for the future?

The Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA) between Chile, New Zealand and Singapore entered into force for New Zealand and Singapore on 7 January 2021 (see Chapter 4). It seeks to address barriers to digital trade between these countries and, potentially, other like-minded partners. It recognises the importance of the digital economy in promoting inclusive economic growth and focuses on the potential for digital technologies to enhance productivity, support innovation and new product creation, and improve market access (Kumar et al., 2020). As the most ambitious agreement of its kind, it provides a possible template to facilitate the growth of digital trade among like-minded Commonwealth developed and developing countries.

The Agreement provides a platform for the parties to discuss emerging digital trade-related issues and seek ways to support interoperability between digital systems within the broader digital economy. While emphasising mutual collaboration, it also recognises the importance of domestic policies and regulations and retains flexibility for the parties to adapt the rules to their local conditions (Elms, 2020). The DEPA covers several policy areas spanning an array of issues related to digital trade and the digital economy (summarised in Table 5.3).

Table 5.3 DEPA key policy areas

| Issue | Highlights and key areas of mutual consideration or collaboration |

|---|---|

| Business and consumer trust |

|

| Business and trade facilitation |

|

| Co-operation and small and medium enterprises (SMEs) |

|

| Data issues |

|

| Digital identities |

|

| Digital inclusion |

|

| Emerging trends and technologies |

|

| Infrastructure |

|

| Innovation and the digital economy |

|

| Intellectual property |

|

| Treatment of digital products and related issues |

|

| Wider trust environment |

|

The DEPA is expected to evolve over time as new technologies emerge and new challenges arise in the digital economy. This creates scope to emulate and refine the agreement when considering the expansion of the digital economy in other Commonwealth countries. Canada has expressed an interest in potentially joining the agreement and recently launched public consultations on the matter (Global Affairs Canada, 2021). It is anticipated that membership in the DEPA will grow as countries look to collaborate to help their citizens and businesses benefit from digital trade and adapt to emerging technologies.

5.8 Develop a newly invigorated Aid for Digital Trade initiative

Commonwealth developed countries such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the UK have been strong advocates and leading donors of AfT to help developing countries with production and supply-side capacity-building. Over the past decade and a half, AfT has made an important contribution to addressing some of the constraints in these areas that have prevented developing countries from participating in and benefiting from international trade. Within the realm of the digital economy, early attention in AfT initiatives was confined mostly to developing network communications infrastructure or digitising import and export procedures as part of efforts to modernise customs (Lacey, 2021). By 2017, however, issues of digital connectivity, e-commerce and readiness to engage in the digital economy were more firmly on the agenda of the AfT community, as evident in an increasing array of AfT interventions promoting online connectivity and aspects of digital inclusiveness. This coincided with efforts by some countries to launch negotiations on e-commerce ahead of WTO MC11, as well as greater attention to e-commerce and digital trade in bilateral, regional and mega-regional FTAs (ibid.).

Data in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Credit Reporting System reveals significant AfT disbursements benefiting ICT. In 2018, African Commonwealth countries received more than US$36 million in AfT resources for ICT, and seven Asian members accrued about $40 million, mostly through contributions from International Development Association donors and Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members (Lacey, 2021). Beyond this, however, it is difficult to disentangle disbursements specifically supporting digitalisation and digital trade from those benefiting other unrelated aspects in available data on AfT flows. More disaggregated data is needed to better understand the extent to which AfT currently supports firms and countries to engage in e-commerce and participate in digital trade (ibid.).

There is a compelling case for directing more donor support to enhance developing countries' participation in digital trade. AfT mechanisms are well suited to a digital focus and likely to produce large impacts in a short period of time and through an efficient allocation of development resources. In a study for the Commonwealth Secretariat, Lacey (2021) suggests that a newly invigorated Aid for Digital Trade agenda could initially focus on four areas:

- Infrastructure. As with broader infrastructure development projects under AfT, interventions to develop digital infrastructure are well suited to Aid for Digital Trade programmes targeting capacity-building and technical assistance.

- Digital skills and adoption. Empowering individuals, consumers, entrepreneurs and businesses with digital skills is key to ensuring inclusive digital transformation, as is facilitating access to and uptake of digital technologies. Aid for Digital Trade can help Commonwealth governments develop supportive policy and regulatory environments that empower citizens and firms to benefit from the digital economy and digital trade.

- E-government. Aid for Digital Trade can help fund the costs incurred when developing and rolling out digital government services that improve the ease of doing business in Commonwealth countries, while also supporting the adoption of digital and online systems.

- Financial inclusion. Digital technologies and platforms play an increasingly important role in enabling access to financial services and broadening financial inclusion. FinTech and digital financial services (e.g. mobile money) are well suited to supporting cross-border e-commerce and digital trade transactions, and assistance for the development and adoption of such innovations could be mainstreamed into Aid for Digital Trade activities.

A dedicated Aid for Digital Trade agenda provides an opportunity to mainstream support for enhanced digital connectivity and adoption into AfT as part of a comprehensive approach to inclusive digital transformation. This can play a central role in helping developing Commonwealth countries harness the manifold development gains from digital trade. However, to maximise the impact of this support, donors must ensure that any Aid for Digital Trade is provided on top of existing official development assistance and AfT flows. Such additionality will ensure any new Aid for Digital Trade agenda does not simply invoke a reallocation of existing aid resources from non-digital to digital sectors, which would only serve to weaken much-needed existing support for developing countries' trade. This new initiative could also be used to assist developing countries and LDCs with digitalising their customs and border processes and building capacity in adopting more paperless trade solutions, as discussed next.

5.9 Digitise trade facilitation and strive for paperless trade

International trade still relies on heavily paper-based processes, with an estimated four billion documents circulating in the trade system. This imposes time, cost and handling inefficiencies for all exporters, but especially MSMEs in Commonwealth developing regions. For example, it is reported that each shipment of roses from Kenya to Rotterdam involves a stack of paper 25 cm high (MacGregor, 2019). Even with some automation, out-dated laws and absence of standards create challenges for business.20

As countries strive to build back better and support trade recovery, an important lesson lies in the advantages afforded by digitising customs and border procedures and moving significantly towards paperless trade. This would result in minimal physical proximity and interaction between customs officials and traders, fewer paper document exchanges and savings of time and cost. For example, it was previously estimated that a 10 per cent reduction in the costs incurred for a good to exit a Commonwealth member country was associated with 7.4 per cent increase in their world exports, which is higher than the global gain of 6.8 per cent, on average. The same reduction in red tape corresponds with a 5 per cent increase in intra-Commonwealth exports, on average (Commonwealth Secretariat, 2018a).

It was highlighted in Chapter 4 that 48 of the Commonwealth's 50 WTO members have ratified the WTO's Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA). The agreement obliges members to deploy a national single window and to use ICT to the "extent practicable" to realise this, drawing on the TFA Facility and other capacity support to develop this infrastructure.21 Many Commonwealth developing countries, including some LDCs, are already implementing such facilities. However, countries can strive to go further by exploring or adopting paperless trade solutions that leverage digitalisation, including blockchains and AI, and ultimately "Rules as Code", which translates regulations to simple, business-friendly language that is readable by both humans and machines (Atkinson, 2020).