- 1.1 Introduction

- 1.2 The Commonwealth’s global trade before the pandemic

- 1.3 Intra-Commonwealth trade before the pandemic

- 1.4 COVID-19 implications for Commonwealth trade

- 1.5 Commonwealth trade prospects towards 2022

- 1.6 Commonwealth trade prospects towards 2022

- 1.7 Conclusion and ways forward

- Annex 1.1

- Annex 1.2

- Annex 1.3

- Annex 1.4

- Annex 1.5

Chapter 1:Commonwealth Trade and the Pandemic

Intra-Commonwealth exports grew spectacularly, at around 10 per cent, during 2017 and 2018. However, COVID-19, together with various global economic exigencies prior to the pandemic, has subdued trade growth and affected exports from all Commonwealth regions. Many countries have been highly exposed to the effects of COVID-19 because of their large services sectors along with existing structural challenges and vulnerabilities; this is especially the case for least developed countries (LDCs) and small states. With the rollout of vaccines, some Commonwealth countries have started to open their economies and resume trade and travel but many others still face the challenge of combating the pandemic.

This chapter analyses the impact of COVID-19 on Commonwealth countries' global and intra-Commonwealth goods and services exports and explores the prospects for trade recovery. Some of the key takeaways are:

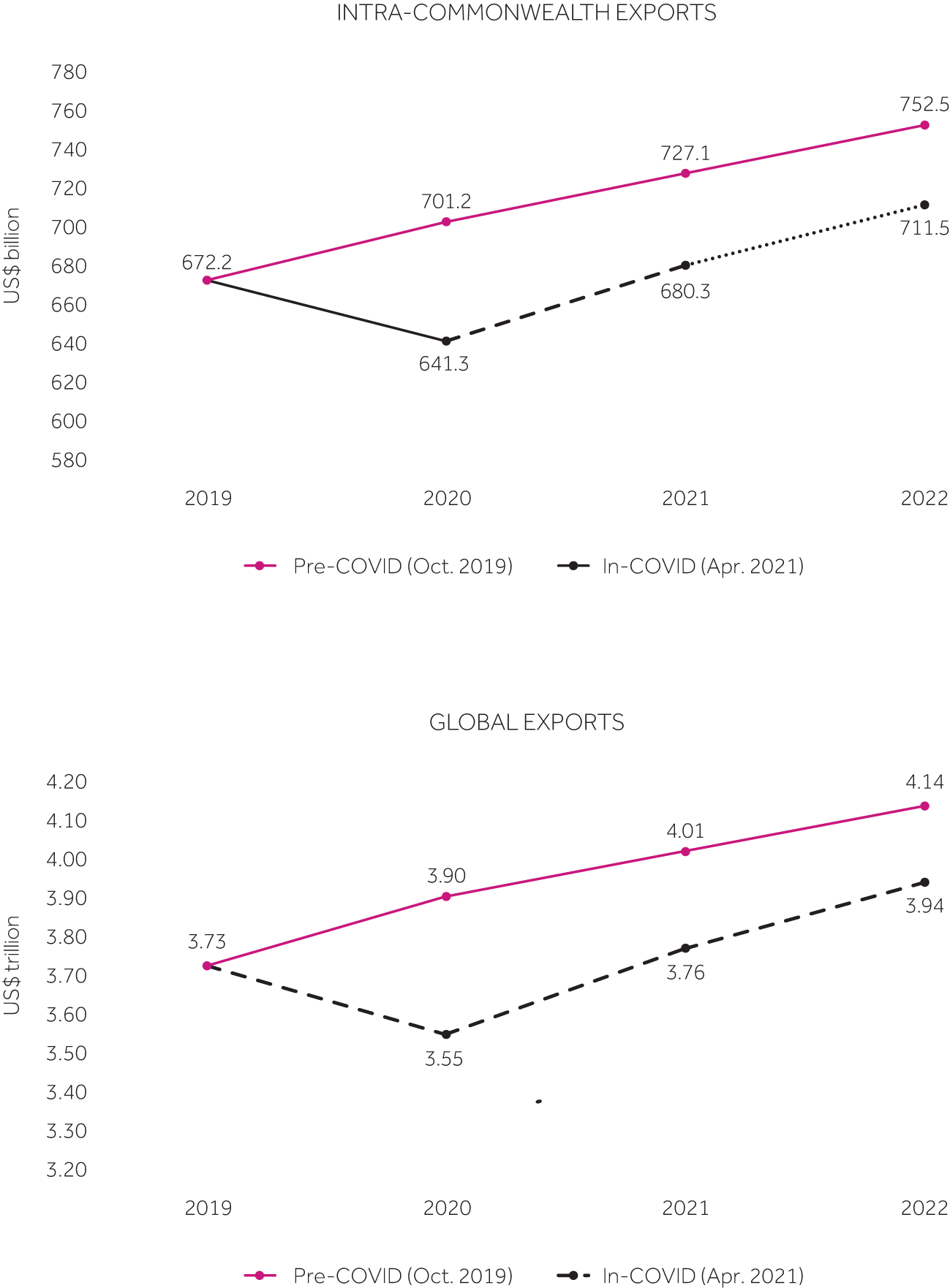

- In 2020, intra-Commonwealth trade was estimated at US$641 billion and could have been $60 billion higher without the pandemic. All Commonwealth regions experienced adverse effects, although the Caribbean and Pacific island countries were relatively more affected because of their dependence on tourism and travel services.

- Intra-Commonwealth trade continues to evolve as member countries deepen existing linkages or diversify trading partners within or outside the Commonwealth. Between 2005 and 2019, 24 member countries considerably increased their share of intra-Commonwealth trade.

- Commonwealth small states depend the most on intra-Commonwealth trade, which represents 28 per cent of their world trade, on average. LDC members, especially Bangladesh and African countries, also have significant exports to Commonwealth markets.

- The Commonwealth advantage remains strong and resilient and could provide a post-pandemic tailwind to support recovery. Revised estimates mean bilateral trade costs between Commonwealth country pairs are 21 per cent lower, on average, compared with non-Commonwealth countries.

- Intra-Commonwealth exports are expected to rebound and surpass US$700 billion by 2022. Countries can leverage digital technologies, utilise trade agreements, promote services co-operation and improve connectivity to boost their trade, while the Commonwealth's youthful population offers another promising dividend for economic recovery.

1.1 Introduction

Commonwealth countries' trade has been affected significantly by the global slowdown in economic growth as a result of COVID-19 and the policy measures used to contain the spread of the virus, including economic lockdowns, travel restrictions and social distancing. The world economy contracted by 3.3 per cent in 2020, with particularly severe impacts on women, youth, the poor and the informally employed. Overall, Commonwealth countries suffered a loss of US$1.15 trillion to their gross domestic product (GDP) compared with the pre-pandemic estimate. During this time, 45 Commonwealth countries fell into recession, while only 9 developing country members registered positive growth - namely, Bangladesh, Brunei Darussalam, Ghana, Guyana, Malawi, Nauru, Tanzania, The Gambia and Tuvalu (see Annex 1.3). By contrast, when the global financial crisis hit more than a decade ago, less than half of the Commonwealth membership went into recession.

This chapter examines the impact of COVID-19 on the performance and prospects of the Commonwealth's global trade and trade among the 54 member countries. The demand, supply and policy shocks of the pandemic have affected countries' trade in multiple ways depending on the structure of their economies, the composition of their exports and their integration into global value chains (GVCs). For example, services like transportation, travel and tourism have been hit hard, and an initial collapse in commodity prices affected the Commonwealth's 35 commodity-dependent exporters. With the easing of lockdowns and restrictions in many countries, and the (uneven) rollout of vaccinations, merchandise trade is starting to lead an economic recovery. However, the revival of the services sector, which is the economic lifeblood of many Commonwealth small states, may take longer.

The chapter consists of seven sections. The next two sections analyse the composition and performance of Commonwealth countries' global and intra-Commonwealth trade during the pre-crisis period to establish a baseline for assessing their vulnerability to the pandemic's effects. Section 1.4 examines some of the actual impacts on the Commonwealth's goods and services trade; Section 1.5 looks specifically at the Commonwealth's 14 least developed countries (LDCs) in this regard.1 Given the focus on immediate economic recovery, Section 1.6 projects the Commonwealth's short-term trade prospects up to 2022. Section 1.7 concludes and offers ways forward.

1.2 The Commonwealth's global trade before the pandemic

1.2.1 Volume of trade and trends

Following a dramatic slowdown in world trade growth in the wake of the global financial crisis more than a decade ago, the trade flows of Commonwealth countries rebounded strongly in 2017 and 2018, with year-on-year growth of around 10 per cent. However, this promising recovery was cut short by economic headwinds, mainly the trade and technology conflict between the USA and China (see Chapter 4), which caused global trade to contract significantly in 2019.2 This global contraction contributed to weak growth in the Commonwealth's exports, which increased by only US$3.5 billion between 2018 and 2019. In 2019, prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the combined value of the Commonwealth's global goods and services exports was $3.73 trillion (Table 1.1). Developing country members contributed around half of these global exports, making up the greater share of goods trade.

Table 1.1 Commonwealth countries' pre-pandemic export profile, 2019

| Value (US$ million) | Share (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goods | Services | Total | Goods | Services | |

| Commonwealth | 2,538,222 | 1,187,637 | 3,725,859 | 68.12 | 31.88 |

| Of which | |||||

| Developed | 1,226,923 | 634,385 | 1,861,307 | 65.92 | 34.08 |

| Developing | 1,279,272 | 553,253 | 1,832,524 | 69.81 | 30.19 |

| Of which | |||||

| Africa | 219,463 | 51,680 | 271,143 | 80.94 | 19.06 |

| Asia | 1,033,714 | 483,121 | 1,516,835 | 68.15 | 31.85 |

| Caribbean SIDS | 13,074 | 15,558 | 28,632 | 45.66 | 54.34 |

| Pacific SIDS | 13,021 | 2,894 | 15,915 | 81.81 | 18.19 |

| Vulnerable groups | |||||

| Small states | 60,602 | 61,734 | 122,335 | 49.54 | 50.46 |

| SIDS | 29,204 | 25,945 | 55,149 | 52.95 | 47.05 |

| LDCs | 62,663 | 16,528 | 79,192 | 79.13 | 20.87 |

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTADstat and WTO-OECD BaTIS datasets)

In absolute terms, the Commonwealth's total exports to the world almost doubled from 2005 (US$2.1 trillion) to 2019 ($3.73 trillion). However, their corresponding share of global exports declined marginally, from 16.2 per cent to 15.1 per cent of world exports ($24.9 trillion) (Figure 1.1). China, which is now the world's largest exporter, contributed to this declining share, as did growth in other large developing countries outside the Commonwealth. At the same time, the share of intra-Commonwealth trade in member countries' overall world trade is rising, having grown from around 16 per cent in 2005 to more than 18 per cent in 2019.

Figure 1.1 Commonwealth countries' global exports of goods and services, 2005-2019

Note: The chart presents total global exports of 54 Commonwealth member countries, good and services combined.

Note: The chart presents total global exports of 54 Commonwealth member countries, good and services combined.Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTADstat and WTO-OECD BaTIS datasets)

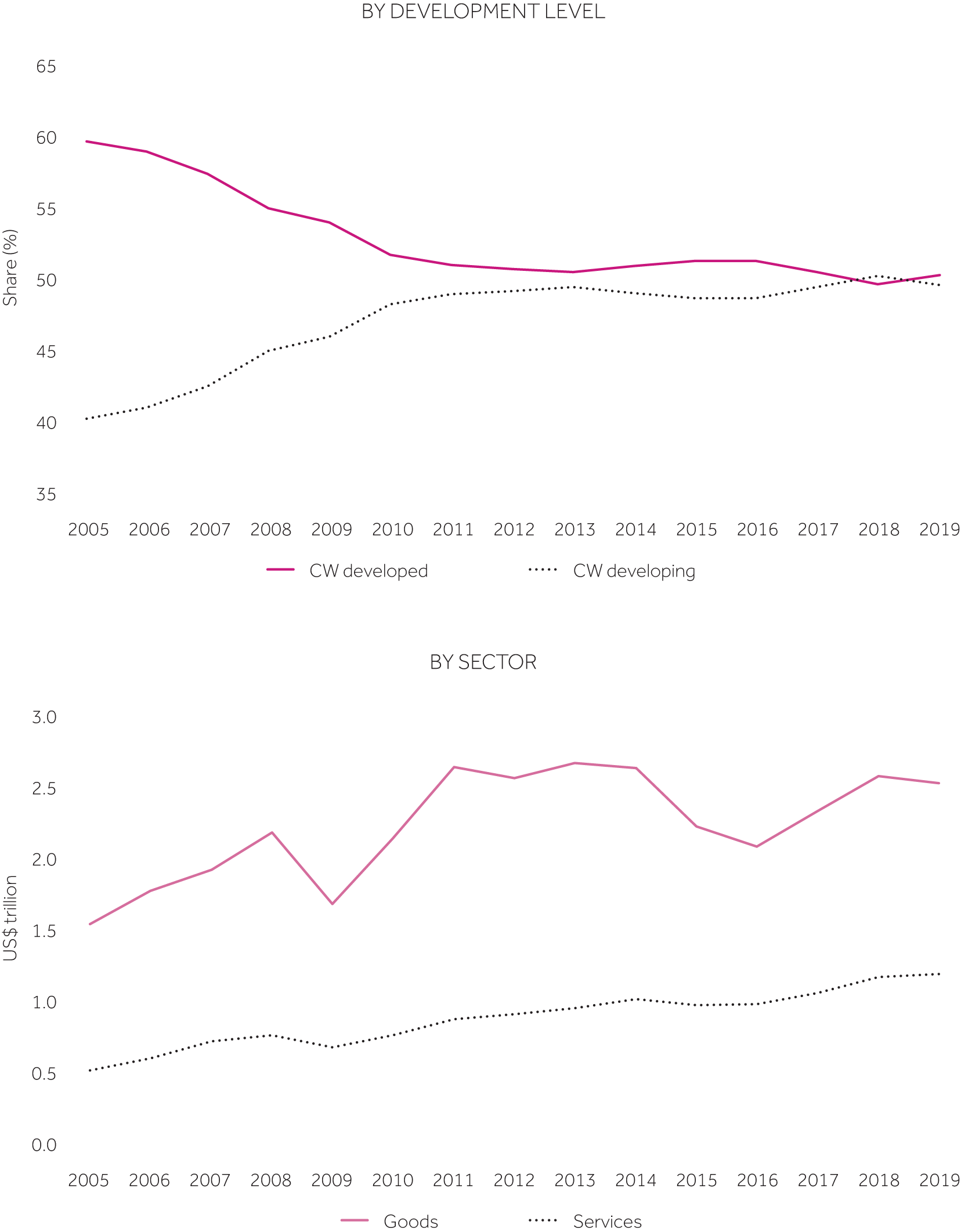

In tandem with changes in the size and relative proportion of the Commonwealth's trade with the world, there have been some significant shifts in the drivers of Commonwealth trade since the 2018 Commonwealth Trade Review. There has been a convergence in the relative contributions of the developed countries - namely, Australia, Canada, Cyprus, Malta, New Zealand and the UK - and the 48 developing country members to the Commonwealth's world trade.3 The share of developing countries in the Commonwealth's total exports increased steadily from 40 per cent in 2005 to nearly 50 per cent in 2017 (Figure 1.2).4 Commonwealth Asian countries, led by India, are driving this convergence, having more than doubled their exports to US$1.51 trillion in 2019 (from $635 billion in 2005). This has translated into a rising share in total Commonwealth trade for Asian countries, from 31 per cent in 2005 to 41 per cent in 2019. The exports of Pacific small island developing states (SIDS) increased nearly threefold to around $15.9 billion in 2019. However, their share in total trade increased only marginally, from 0.3 per cent in 2005 to 0.4 per cent in 2019.

Figure 1.2 Evolution of Commonwealth members' exports, by development level and sector, 2005-2019

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTADstat and WTO-OECD BaTIS datasets)

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTADstat and WTO-OECD BaTIS datasets)

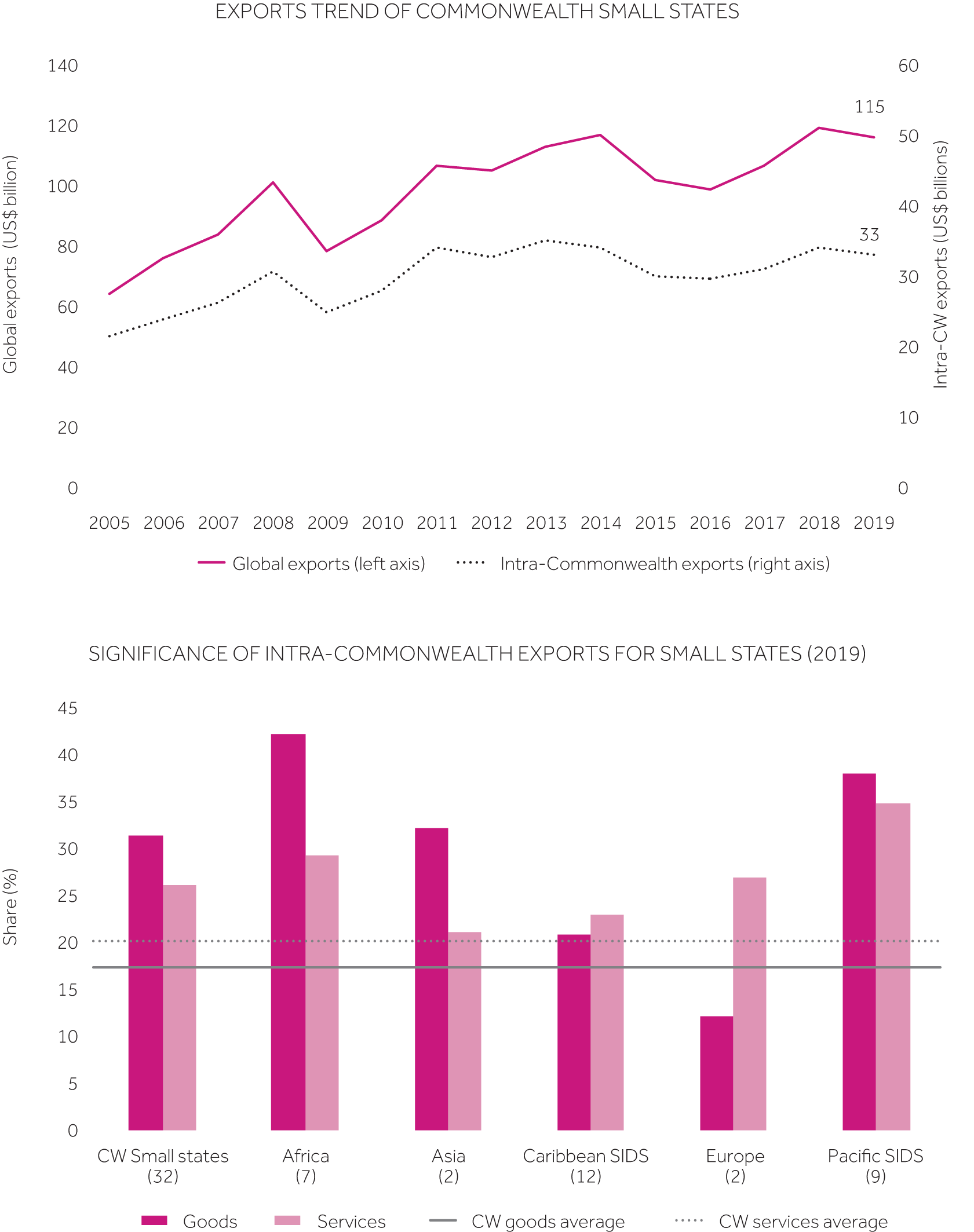

Pre-pandemic headwinds also affected the trade flows of the Commonwealth's 32 small states. In 2019, their combined global exports were US$115 billion while their intra-Commonwealth exports were around $33 billion, almost $1 billion less than the level reached in 2018 (Figure 1.3). In relative terms, small states' goods and services exports amount to 0.45 per cent of global exports and 3 per cent of overall Commonwealth exports. Malta and Cyprus contribute the largest share - about one-third (or $37 billion) - of small states' exports. The top three exporters from developing regions were Papua New Guinea ($11.6 billion), Brunei Darussalam ($7.6 billion) and Jamaica ($6 billion) in 2019.

Figure 1.3 Trade performance and composition of Commonwealth small states' exports, 2005-2019

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTADstat and WTO-OECD BaTIS datasets)

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTADstat and WTO-OECD BaTIS datasets)

Most of the trade challenges facing small states precede COVID-19 and involve excessively high trade costs as a result of their small size and remote geography, diseconomies of scale, inadequate infrastructure, concentrated production and export sectors, and vulnerability to climate change and recurrent natural disasters. The trade and sustainability challenges, especially in the fisheries and tourism sectors, will now have to be tackled in tandem through devising post-COVID-19 recovery and resilience strategies, as discussed in Chapter 5.

1.2.2 Structure and composition of trade

More than two-thirds of the Commonwealth's global trade is in merchandise. In 2019, goods exports were worth US$2.5 trillion (68 per cent of overall trade) while services contributed $1.18 trillion (32 per cent) (Table 1.1).

The UK was the largest exporter of both goods and services, accounting for around 24 per cent of total Commonwealth trade. In 2019, the UK's goods exports were about US$468 billion (19 per cent of total Commonwealth goods exports) while its services exports were $416 billion (35 per cent of total Commonwealth services exports).

Only a few large economies within each Commonwealth region drive the Commonwealth's global exports. Ten countries accounted for 94 per cent of total merchandise exports5 and 93 per cent of services exports6 in 2019 (Annex 1.1). Most of these economies contracted as a result of the pandemic. This affected their overall trade flows, as well as intra-Commonwealth trade, in 2020. The pace of economic recovery in these countries will determine the prospects for trade growth beyond COVID-19.

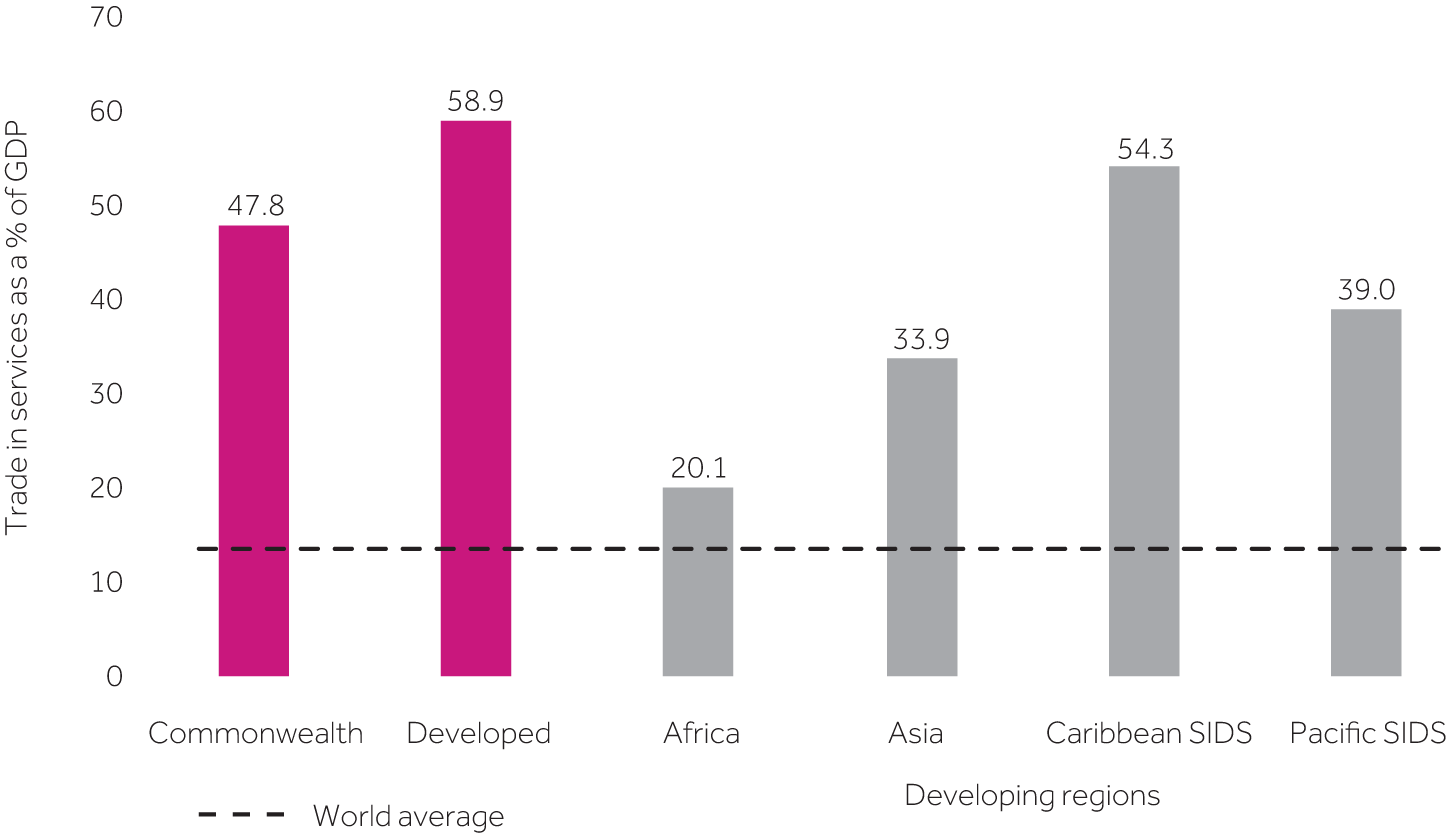

Commonwealth countries are active participants in the global services economy. The contribution of services exports to GDP varies enormously across developed and developing countries and regions (Figure 1.4). Developed countries have the highest share, at almost 60 per cent. Among developing countries, the Caribbean and Pacific regions have larger proportions of services exports in their GDP (54 per cent and 39 per cent, respectively). This owes to the predominance of tourism and travel services, especially in the Caribbean. The share of services exports in the GDP of the Asian (34 per cent) and African (20 per cent) regions is relatively small but still higher than the world average.

Figure 1.4 Share of Commonwealth services exports in GDP by region, 2019

Note: Nauru excluded owing to non-availability of data; the dotted line indicates the world average.

Note: Nauru excluded owing to non-availability of data; the dotted line indicates the world average.Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using WDI data)

Merchandise exports

Commonwealth developing countries are the largest merchandise exporters, at US$1.28 trillion in 2019. However, there is wide variation within the Commonwealth's developing regions, as the following stylised facts reflect.

Asian members are overwhelmingly the leading exporters of goods, with exports valued at US$1.03 trillion in 2019 (68 per cent of their total exports). Three Asian countries accounted for around 40 per cent of these exports: Singapore ($390 billion or 16 per cent), India ($323 billion or 13 per cent) and Malaysia ($238 billion or 9 per cent).

For Commonwealth Africa, goods contributed more than 80 per cent of their exports in 2019 (Annex 1.1). Three sub-Saharan African (SSA) members accounted for almost 80 per cent of the region's total merchandise exports: South Africa ($90 billion or 41 per cent), Nigeria ($65 billion or 29 per cent) and Ghana ($16 billion or 8 per cent).

The Pacific SIDS depend the most on goods exports (82 per cent) and the least on services (18 per cent). In 2019, Papua New Guinea was the largest exporter (US$11.41 billion), accounting for more than 87 per cent of the region's exports and almost 10 times the value of the next ranking country, Fiji ($1.61 billion).

The Caribbean SIDS have narrow production sectors, such as offshore oil and gas, fisheries and commodities like bananas and sugar. In 2019, Trinidad and Tobago accounted for two-thirds of the region's goods exports, valued at US$8 billion, followed by Guyana ($1.7 billion) and Jamaica ($1.6 billion).

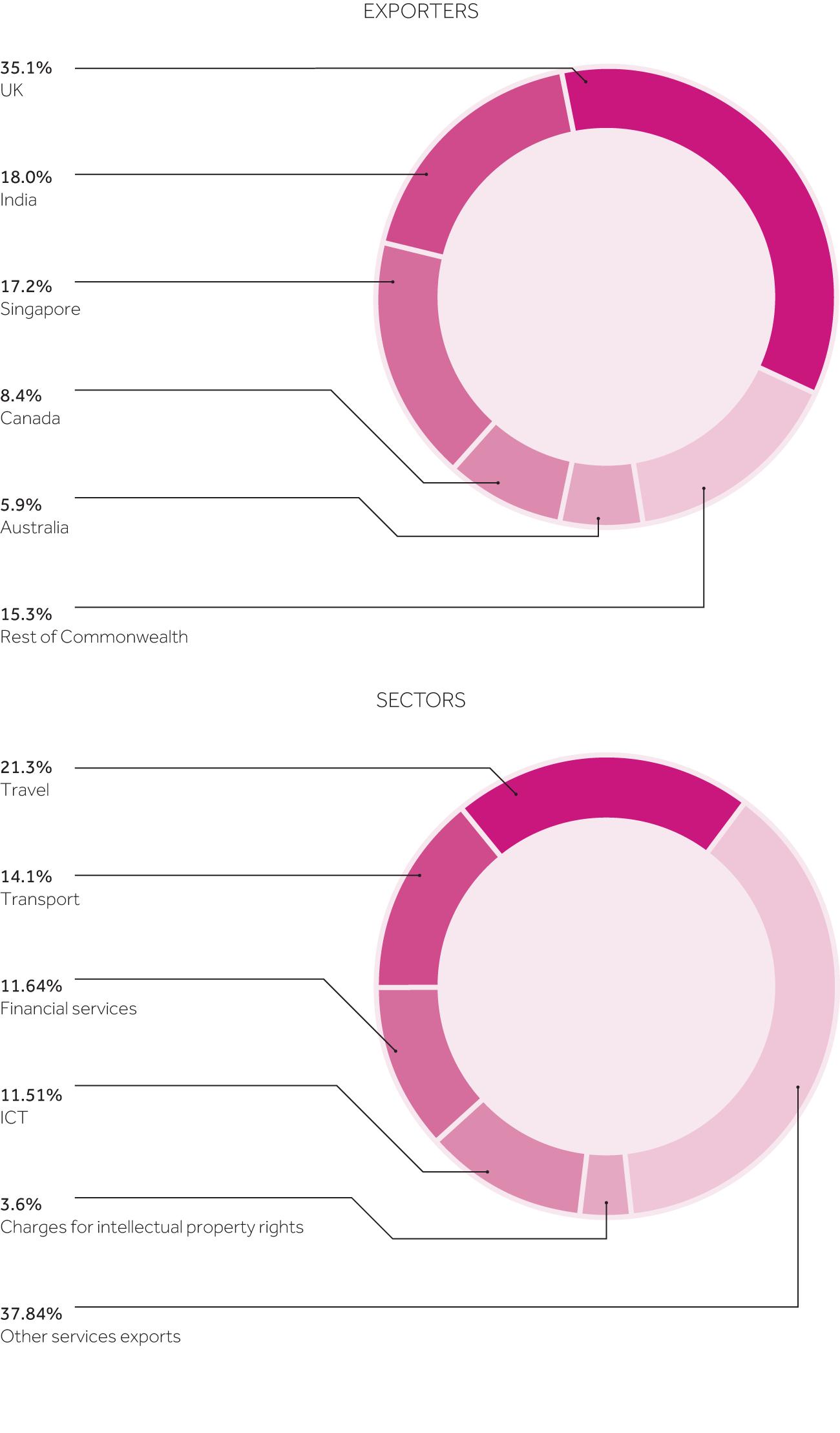

Services exports

Commonwealth developed countries are the largest exporters of services, valued at US$634 billion in 2019 (Table 1.1). Among these countries, the UK supplied almost one-third of the Commonwealth's services exports (see Figure 1.5), of which around one-third was financial services (US$80 billion) and travel services ($50 billion). However, their share in overall services exports is declining - from 69 per cent in 2005 to 53 per cent in 2019 - because developing countries, especially Asian members, are increasingly important players in this sector. India and Singapore together accounted for around one-third of the Commonwealth's services exports, comprising mainly business services and information technology (IT) support.

Figure 1.5 Leading services exporters and key services sectors, 2019

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using WTO-OECD BaTIS dataset)

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using WTO-OECD BaTIS dataset)

Commonwealth African members have one of the lowest shares of services exports (19 per cent). South Africa, Ghana and Kenya are the largest services suppliers, accounting for 57 per cent of the region's services exports; Rwanda is also an important services player. Among the SSA membership, only two countries export more services than goods - namely, Mauritius (US$2.9 billion in 2019) and Seychelles ($1.1 billion). More than half of these exports were travel or tourism-related.

The Caribbean SIDS have the largest orientation towards trade in services; around 54 per cent of their exports comprise services, especially related to tourism. The COVID-19 pandemic has affected these sectors significantly.

Travel, an aggregate of tourism and business travel, is the largest category, amounting to around one-fifth of total services exports. The other three big services categories are transport, information and communication technology (ICT) and financial services. These three groups combined account for around 40 per cent of services exports (Figure 1.5). Given the importance of tourism in Commonwealth services trade, it is likely that the COVID-19 pandemic, which has made in-person travel both more difficult and less appealing to consumers, has had a major depressive effect on this trade. ICT and financial services, by contrast, could see different dynamics at play: in-person interactions have become more difficult but there has also been some shift towards online service provision (Shepherd and Shingal, 2021; see Chapter 2). The same applies to intra-Commonwealth services trade in these sectors.

1.3 Intra-Commonwealth trade before the pandemic

1.3.1 Volume of trade and trends

Intra-Commonwealth trade is historically and commercially significant for many members, especially small states, LDCs and SSA countries. The "Commonwealth advantage" has helped build, strengthen and sustain many of these trading relationships (Box 1.1). Factors such as historical ties, familiar legal and administrative systems, the use of largely one language, English, as the means of communicating with foreign partners, and large and dynamic diasporas underpin this advantage, which is particularly significant for trade in services (Commonwealth Secretariat, 2015).

The Commonwealth advantage remains compelling for many member countries and could provide a post-pandemic tailwind to support recovery from the economic consequences of the pandemic. Indeed, re-examination of the Commonwealth advantage with the availability of a refined bilateral trade costs dataset for a longer period reveals the resilience and strengthening of this cost advantage for trading between Commonwealth countries, to 21 per cent, on average.

Box 1.1 Trade costs advantage in intra-Commonwealth trade

The Commonwealth advantage implies that Commonwealth member countries have on average 19 per cent lower trade costs in their bilateral trade than in trade with non-member countries (Commonwealth Secretariat, 2015). The revised estimates calculated with the most up-to-date datasets (1995-2017) indicate that, on average, aggregate bilateral trade costs between Commonwealth country pairs are lower to the tune of around 21 per cent7 compared with the cost of trading with non-Commonwealth countries (Table 1.2). The trade cost advantage holds for both agricultural products and manufactured goods (columns 2 and 3) but the magnitude of the effect varies marginally across sectors, mainly because of data limitations resulting in different sample sizes. A slightly lower coefficient in the manufacturing sector (column 3), besides indicating the variation in sample size, could reflect relatively lesser trade costs owing to lower tariffs in manufacturing sectors.

Table 1.2 The Commonwealth effect on trade costs

| Overall | Agriculture | Manufacturing | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Commonwealth membership | -0.192*** | -0.186*** | -0.171*** |

| Distance (km) | 0.443*** | 0.373*** | 0.473*** |

| Origin-year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dest.-year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sample size | 333,668 | 184,824 | 298,968 |

| CW countries | 53 | 51 | 52 |

| Period | 1995-2017 | 1995-2017 | 1995-2017 |

| R-squared | 0.71 | 0.58 | 0.71 |

Note: The dependent variable is bilateral trade costs. The estimated coefficients are statistically significant at 1 per cent level, as indicated by ***. Estimated using the OLS panel regression method.

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (estimated using World Bank Trade Costs dataset)

Many factors, such as distance, language, legal systems and tariffs, influence trade costs, with transport just one of the overall costs of international trade. This means the data for bilateral trade costs is very limited. To circumvent this challenge, Arvis et al. (2016) use an inverse gravity approach to infer bilateral trade costs between countries. This approach has a micro-foundation as it is based on a theoretical model developed in Novy (2013). Following this approach, the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) and the World Bank have developed a global database on bilateral trade costs for 180 countries over 1995-2017, including 53 Commonwealth countries (excluding Solomon Islands). These bilateral trade costs are interpreted in a similar way to ad valorem equivalents.

The dataset of Arvis et al. (2016) has been used to empirically test whether the Commonwealth is indeed associated with reduced trade costs between its members. A regression of bilateral trade costs on a binary indicator for whether the two countries are Commonwealth members is estimated. The results, shown in columns 1 and 2 of Table 1.2, provide strong evidence that the Commonwealth is associated with lower trade costs. The estimated coefficient for the binary indicator, the Commonwealth membership, is statistically significant at a 1 per cent significance level. Even when distance in combination with time-varying fixed effects for countries is accounted for, bilateral trade costs are 21 per cent lower for Commonwealth partners than for other pairs of countries (i.e. Commonwealth and non-Commonwealth or both countries non-Commonwealth).

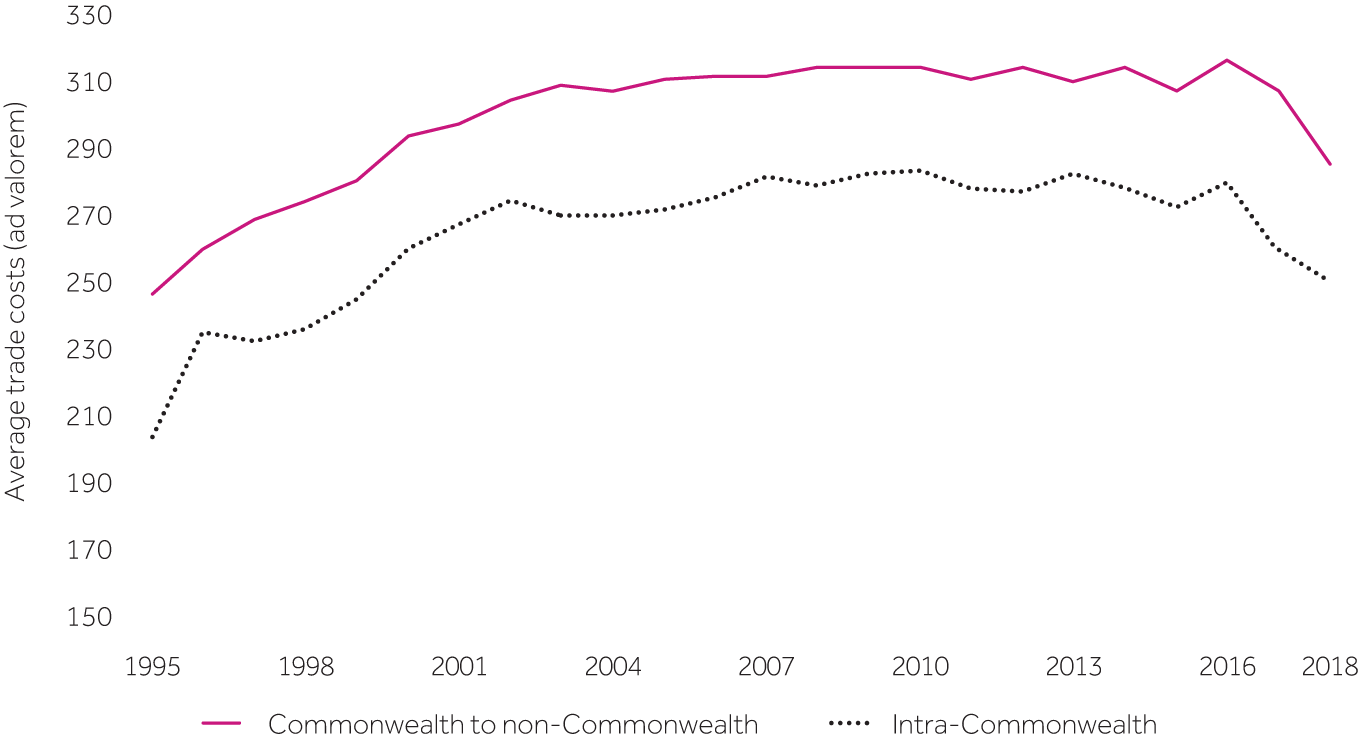

An analysis of bilateral trade costs for different sample partners reveals that the trade costs between Commonwealth country pairs have been consistently lower over time (Figure 1.6). For example, in 2000, average bilateral trade costs for intra-Commonwealth partners were 260 per cent as against 293 per cent for Commonwealth and non-Commonwealth bilateral pairs. These results seem to be consistent with the findings of rising intra-Commonwealth trade as a share of the Commonwealth's global trade over time.

Figure 1.6 Share of average trade costs between Commonwealth trade partners vs. others, 1995-2018

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using World Bank Trade Costs dataset)

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using World Bank Trade Costs dataset)

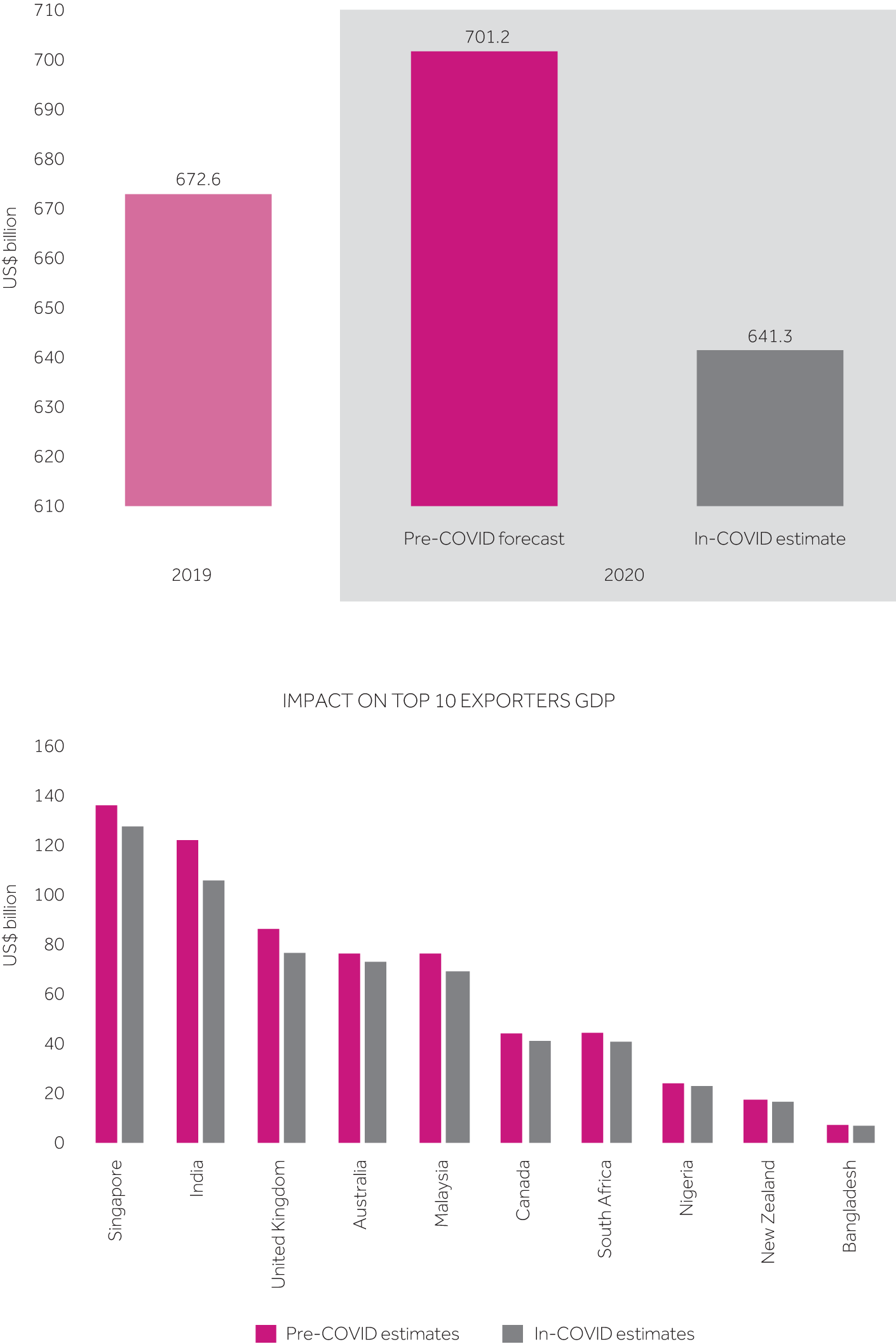

Intra-Commonwealth trade in goods and services was worth US$672 billion in 2019, with almost two-thirds of trade being in merchandise (Table 1.3). The growth of intra-Commonwealth trade, like global trade, has been constrained by various pre-COVID-19 headwinds.

Table 1.3 Share of goods and services in intra-Commonwealth exports, 2019

| Goods Value (US$ million) | % | Services Value (US$ million) | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commonwealth | 433,892 | 65 | 238,755 | 35 |

| By development | ||||

| Developed | 125,026 | 57 | 93,587 | 43 |

| Developing | 308,866 | 68 | 145,168 | 32 |

| By region | ||||

| Africa | 75,815 | 85 | 13,539 | 15 |

| Asia | 225,386 | 64 | 127,067 | 36 |

| Caribbean and Americas | 29,317 | 65 | 15,514 | 35 |

| Caribbean SIDS | 2,737 | 43 | 3,559 | 57 |

| Europe | 39,108 | 43 | 51,360 | 57 |

| Pacific | 64,266 | 67 | 31,275 | 33 |

| Pacific SIDS | 4,927 | 83 | 1,003 | 17 |

Note: The percentage share indicates the share of goods and services in the corresponding group.

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTADstat and OECD-WTO BaTIS datasets)

Developing countries are the largest exporters of goods (68 per cent); in absolute terms, they export 2.5 times more merchandise than the developed economies. As with the global pattern, developed countries accounted for a larger share of intra-Commonwealth services trade (43 per cent) in 2019.

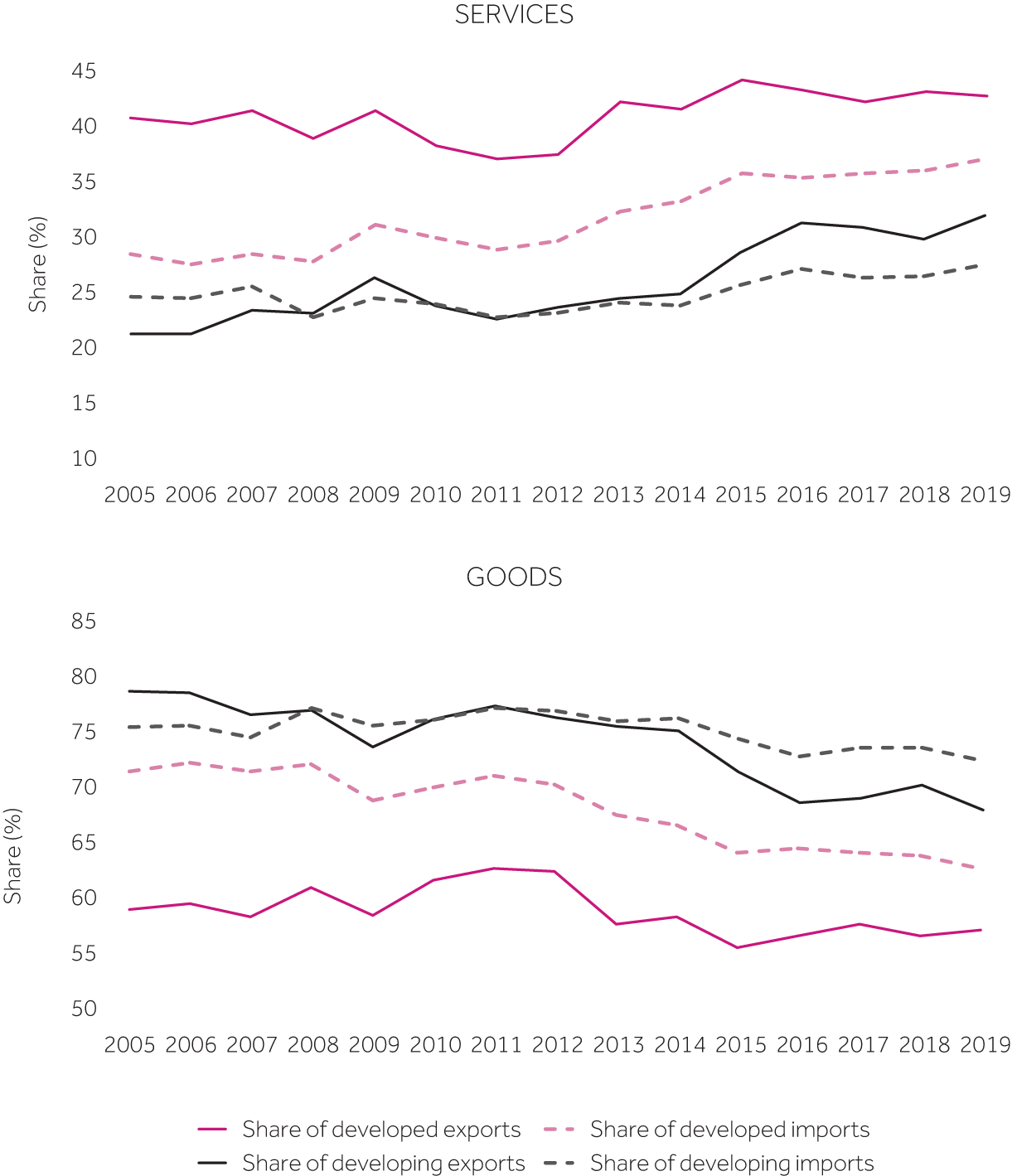

Intra-Commonwealth merchandise trade has gradually increased over time, from US$240 billion in 2005 to $433 billion in 2019. The corresponding increase in services trade was much larger, from $98 billion in 2005 to $238 billion in 2019 - an almost three-fold increase (Figure 1.7).

Figure 1.7 Trends in intra-Commonwealth exports of goods and services, 2005-2019

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated from UNCTADstat and OECD-WTO BaTIS datasets)

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated from UNCTADstat and OECD-WTO BaTIS datasets)

The share of intra-Commonwealth trade in Commonwealth members' total world trade has been rising since 2005, reaching a peak of 19.3 per cent in 2012 before a global trade slowdown (2012-2015) constrained growth. In 2018 and 2019, the share of intra-Commonwealth trade remained steady at around 18 per cent.

Commonwealth developing countries drive intra-Commonwealth trade flows. Over time, the developing countries' export share increased (from 60 per cent in 2005 to 67 per cent in 2019), while their exports almost doubled in value terms, going from US$204 billion to more than $450 billion in the same period.8 This shift owes largely to the greater expansion of trade by Asian member countries, which increased their intra-Commonwealth share to almost 53 per cent in 2019.

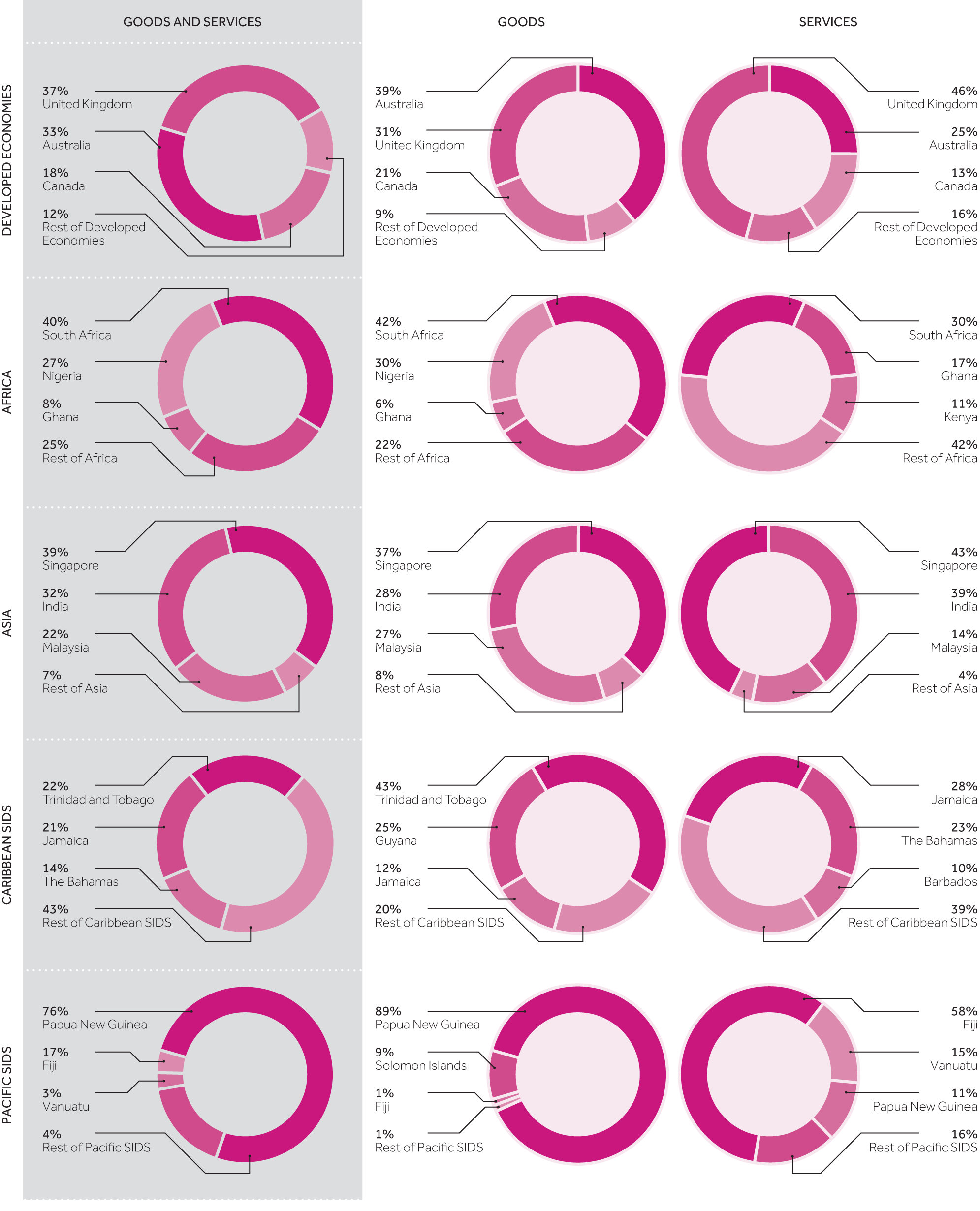

Overall, reflecting the global pattern, only a few large economies drive intra-Commonwealth trade. The UK alone accounted for around 40 per cent of the share of the developed economies in 2019. The UK also led services exports (46 per cent), while Australia had the largest share of merchandise trade (39 per cent). Among developing countries, Singapore, India and Malaysia together accounted for 93 per cent of exports of goods as well as services for Asian members (Annex 1.1).

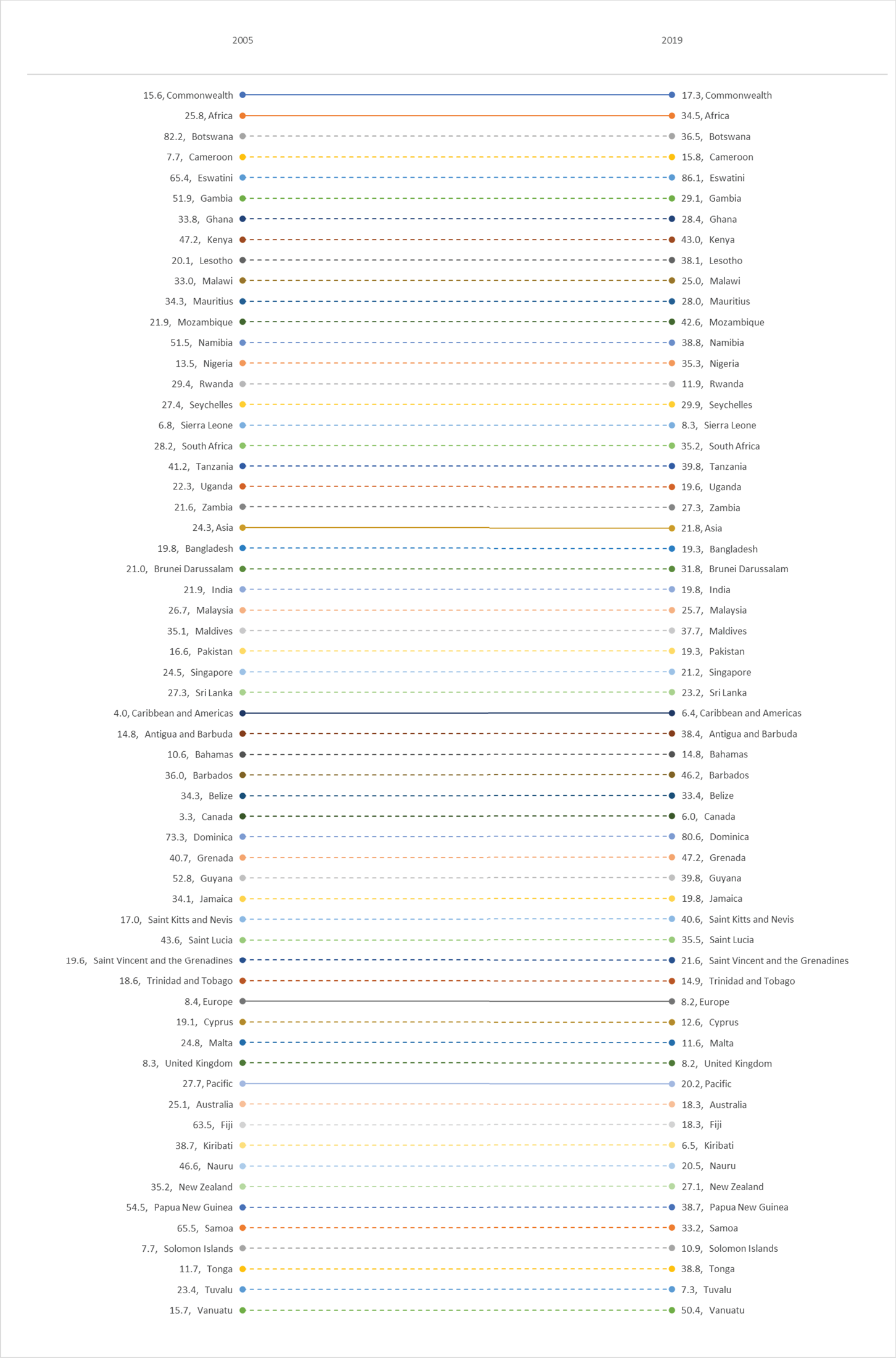

Intra-Commonwealth trade has evolved as member countries deepen existing trade linkages or diversify their trading partners within or outside the Commonwealth. Between 2005 and 2019, 24 member countries considerably increased their share of intra-Commonwealth trade, including several small states (Annex 1.4). For instance, over this period, the share of intra-Commonwealth trade in Vanuatu's exports rose from 15 per cent to around 50 per cent, trading largely with Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, Fiji and Malaysia. Other members successfully diversified their trading partners, resulting in lower shares of intra-Commonwealth trade.

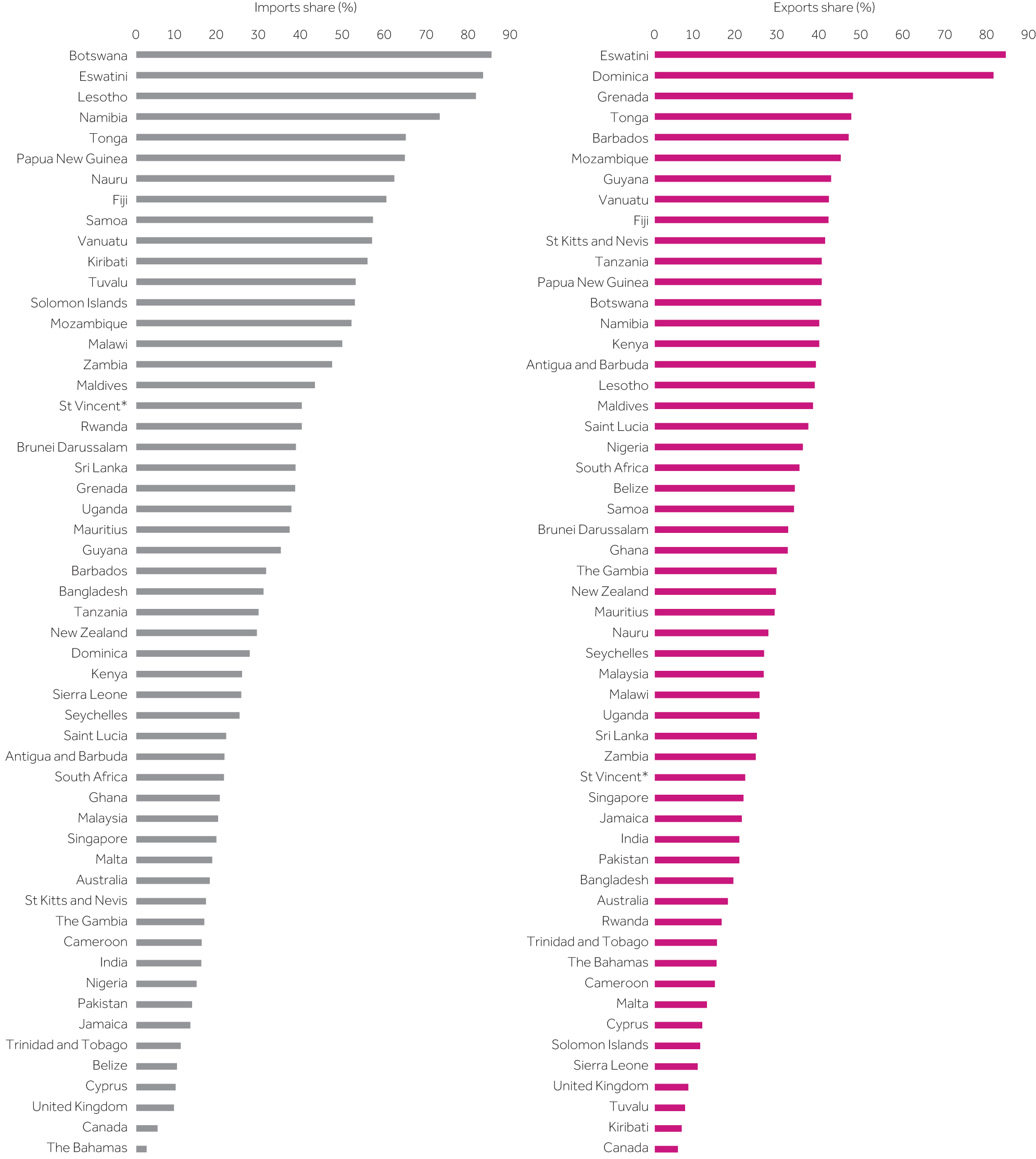

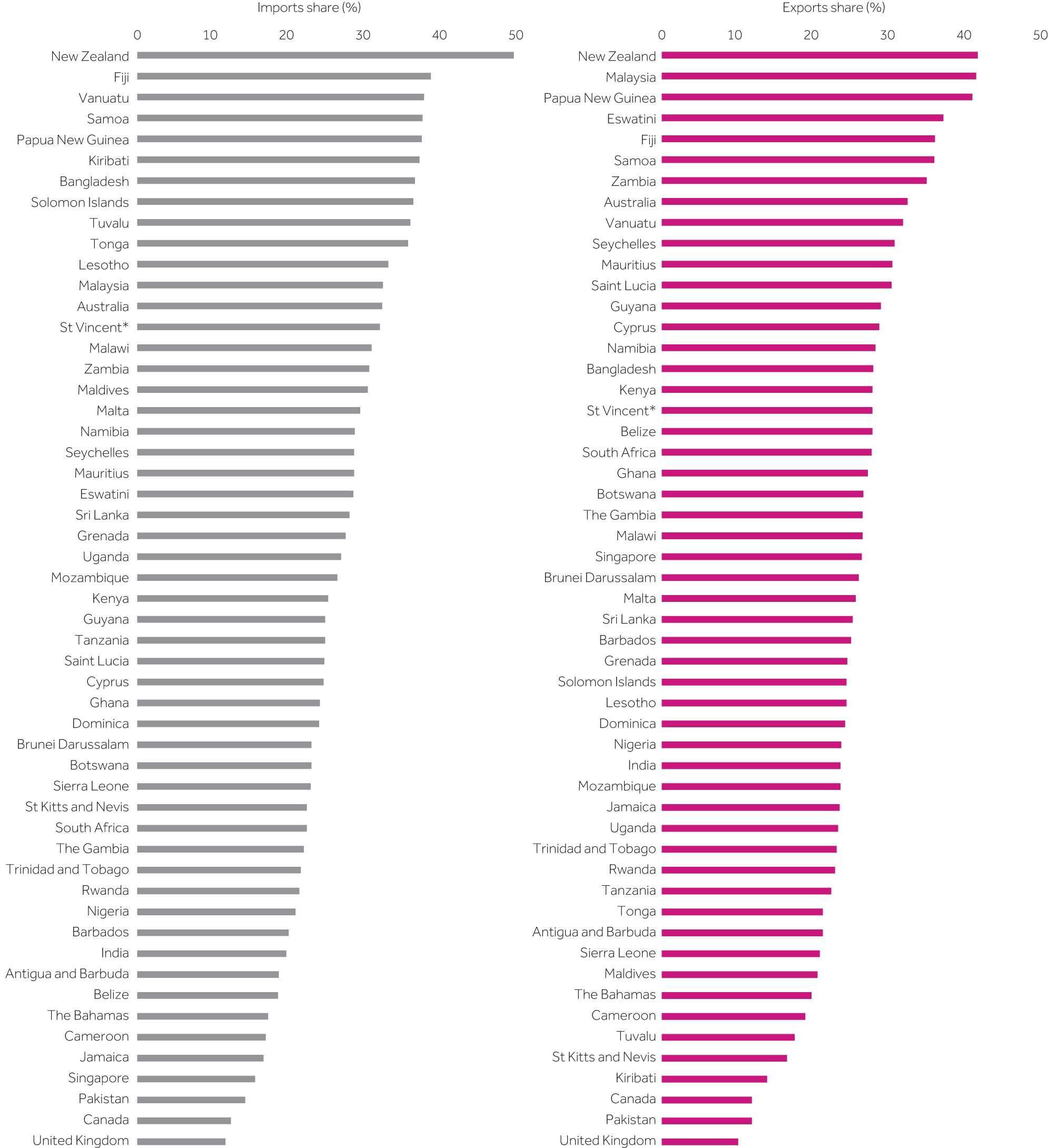

Commonwealth small states depend the most on intra-Commonwealth trade, which represents 28 per cent of their world trade, on average. Their share of merchandise in intra-Commonwealth exports (31 per cent) is considerably higher than that of services (26 per cent). However, there is wide variation among these small economies (Figure 1.8). During 2017-2019, the share of intra-Commonwealth exports ranged from 6 per cent (for Kiribati) to more than 80 per cent (for Eswatini), while imports vary from 10 per cent (for The Bahamas) to 82 per cent (for Botswana). Most of this intra-Commonwealth trade takes place regionally. The prominence of intra-Commonwealth imports for Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho and Namibia owes to their membership, together with South Africa, in the Southern African Customs Union (SACU). Dominica and Grenada's high export shares owe to their membership in the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) and the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS). These economies have also gained prominence in intra-Commonwealth services exports (Figure 1.9).

Figure 1.8 Relative significance of intra-Commonwealth merchandise trade in member countries' total trade, 2017-2019 average

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTADstat dataset) *St Vincent and the Grenadines due to space constraints

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTADstat dataset) *St Vincent and the Grenadines due to space constraints

Figure 1.9 Relative significance of intra-Commonwealth services exports in member countries' total services exports, 2017-2019 average

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using WTO-OECD BaTIS dataset) *St Vincent and the Grenadines due to space constraints

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using WTO-OECD BaTIS dataset) *St Vincent and the Grenadines due to space constraints

The Commonwealth's 14 LDCs also depend significantly on intra-Commonwealth trade; this is especially the case for Bangladesh and the African LDCs. In absolute terms, Bangladesh is the largest LDC exporter, sending almost three times more goods and services combined to the Commonwealth than the next ranked countries - Tanzania, Zambia and Mozambique (Annex 1.5). However, the nine SSA LDCs contributed just over half of LDCs' intra-Commonwealth exports (US$19.01 billion) in 2019.

Intra-African trade accounts for a large share of this intra-Commonwealth LDC trade. Around 15-30 per cent of the exports of four LDCs - Zambia, Mozambique, Tanzania and Uganda - are with other African Commonwealth countries. LDCs' structure of intra-Commonwealth trade closely mirrors that of their global exports. Although merchandise exports dominate their trade flows, the share of services is slightly higher than in their global exports. For the Pacific LDCs, services constitute more than 70 per cent of their intra-Commonwealth exports.

1.3.2 Regional distribution of intra-Commonwealth trade

Intra-Commonwealth trade is highly regional in nature, especially because of the operations of regional production networks and supply chains, which COVID-19 has brought into greater focus. Moreover, trade between Commonwealth countries is found to be more than three times higher when they belong to an existing trade agreement (Commonwealth Secretariat, 2018a; see Chapter 4). Five Commonwealth regions are used to analyse intra-Commonwealth trade - and investment (see Chapter 3) - flows: Africa, Asia, Caribbean and Americas (Canada and the Caribbean SIDS), Europe and the Pacific (Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific SIDS).

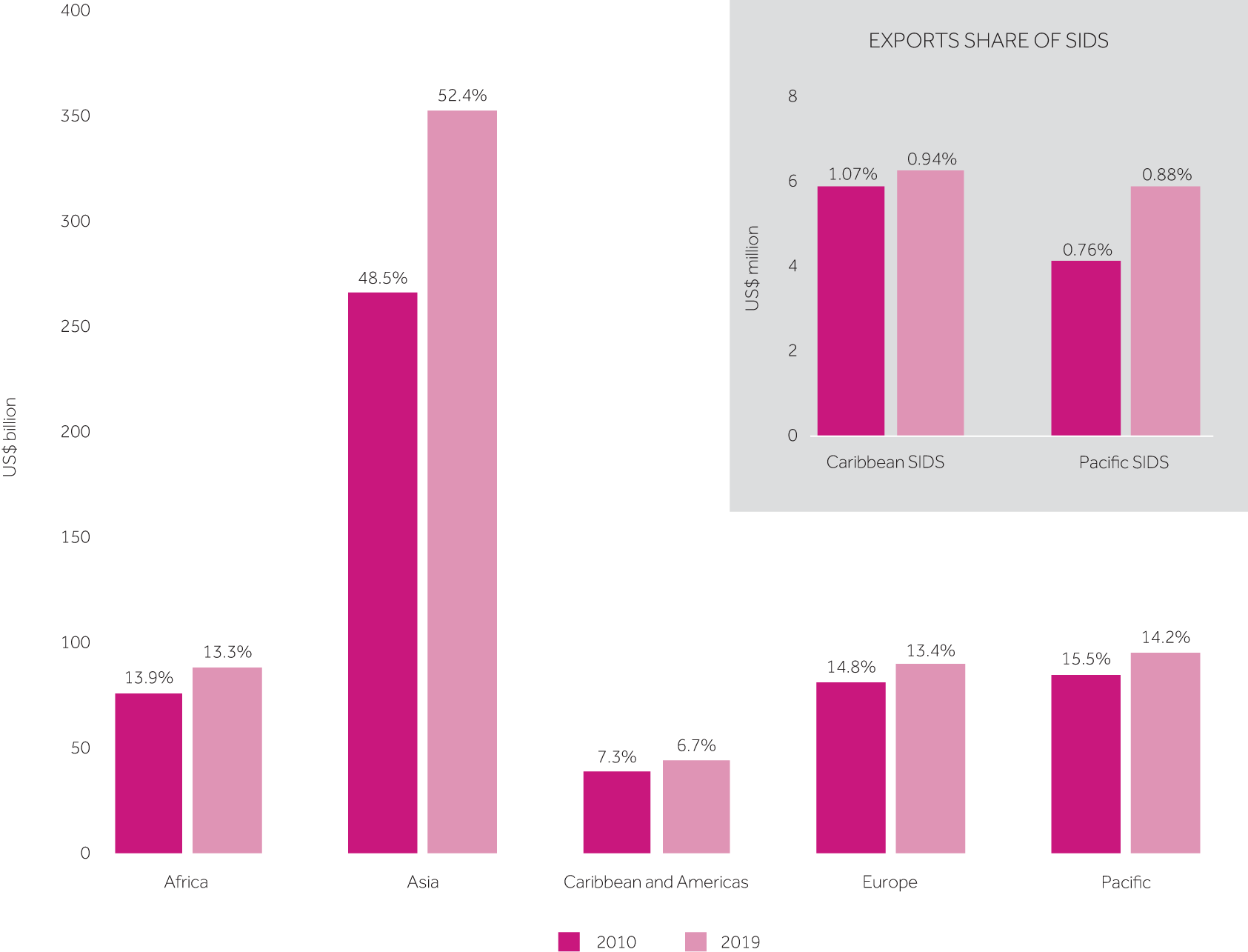

Commonwealth Asia now contributes more than half of intra-Commonwealth trade. The share of the Asian economies had risen by 4 percentage points to 52.5 per cent in 2019 (Figure 1.10). During the same period (between 2010 and 2019), the shares of the African, Caribbean, Pacific and European members declined marginally, although their exports did increase in absolute terms. In the Pacific region, Australia and New Zealand drive intra-Commonwealth trade; Canada is the leading exporter in the Caribbean and Americas region. Though Caribbean SIDS increased their exports in value terms, their relative share of intra-Commonwealth trade declined from 1.1 per cent in 2010 to 0.9 per cent in 2019. The Pacific SIDS, on the other hand, registered a marginal increase both in value and in relative terms. This reflects the large trade orientation of Pacific islands towards Australia and New Zealand.

Figure 1.10 Regional distribution of intra-Commonwealth trade, 2010 vs. 2019

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTADstat and WTO-OECD BaTIS datasets)

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTADstat and WTO-OECD BaTIS datasets)

In Commonwealth Africa, more than 75 per cent of exports originated in three members: South Africa, Nigeria and Ghana. South Africa is the largest intra-Commonwealth exporter, for both goods and services, accounting for 42 per cent of merchandise exports and 30 per cent of services exports. Thereafter, Nigeria and Ghana are the two largest merchandise exporters, while Ghana and Kenya are the largest services exporters, in that order (Figure 1.11). Rwanda is also a prominent services exporter, especially given its attraction as a tourist destination, mainly for gorilla watching.

Figure 1.11 Share of goods and services exports for leading exporters, by region, 2019

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTADstat and WTO-OECD BaTIS datasets)

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTADstat and WTO-OECD BaTIS datasets)

Looking specifically at the Caribbean SIDS, three economies (Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica and The Bahamas) accounted for 57 per cent of the Caribbean SIDS' intra-Commonwealth exports in 2019. Trinidad and Tobago accounted for 43 per cent of merchandise exports, followed by Guyana and Jamaica; Jamaica, The Bahamas and Barbados are leading services traders.

Among the Pacific SIDS, two economies (Papua New Guinea and Fiji) accounted for 93 per cent of the Pacific islands' intra-Commonwealth exports in 2019. The trade distribution is very much concentrated: Papua New Guinea alone accounted for 90 per cent of merchandise exports while Fiji accounted for around 60 per cent of services exports.

1.3.3 Structure and composition of intra-Commonwealth trade

Intra-Commonwealth merchandise trade

Amid a global trade contraction, the value of intra-Commonwealth merchandise trade in 2019 dropped to US$433 billion, a loss of $8 billion on 2018. The abrupt recessions caused by COVID-19 in several large Commonwealth traders, including India, Singapore, South Africa and the UK, further dampened trade growth in 2020.

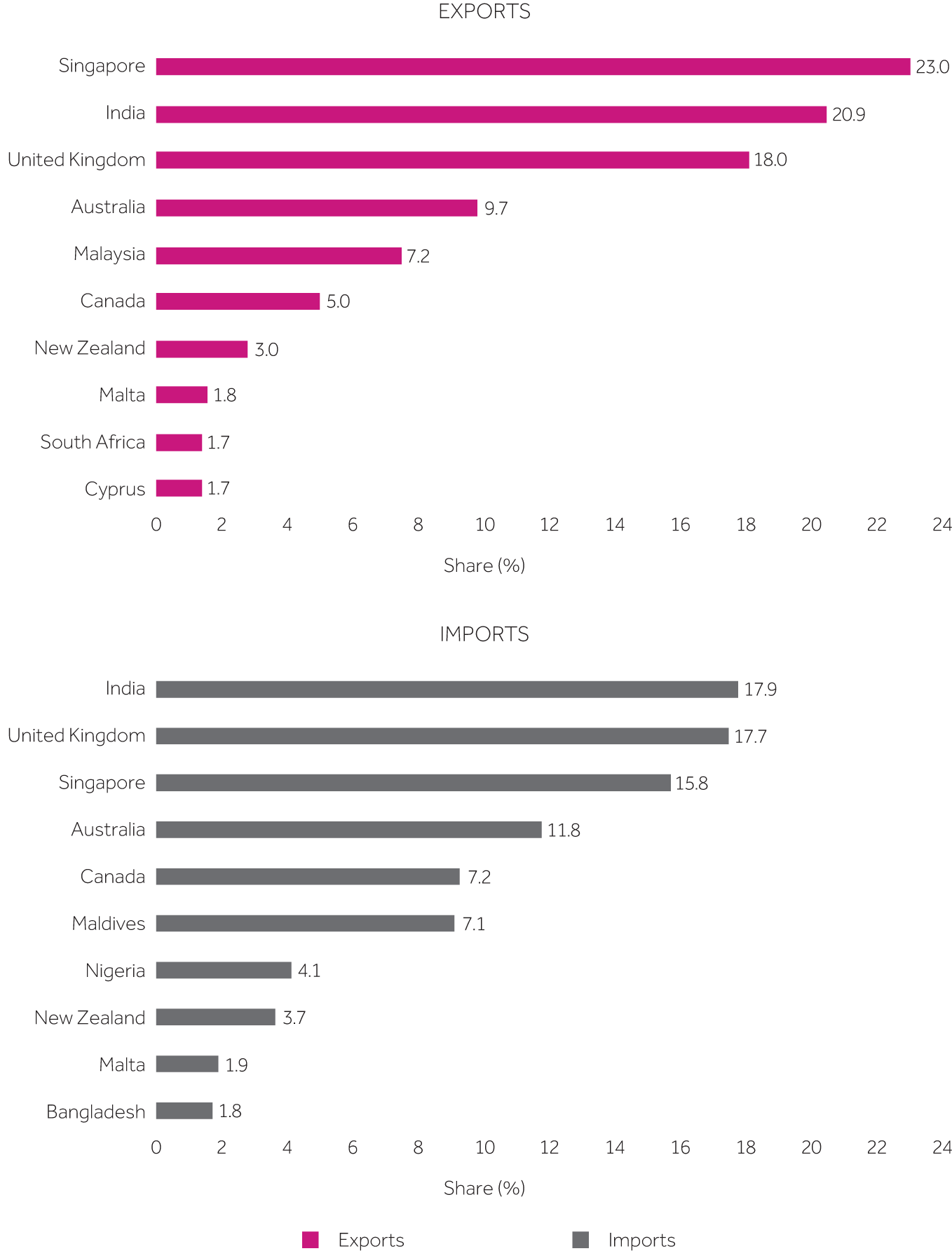

Similar to the pattern of Commonwealth total trade, Asian countries continue to drive intra-Commonwealth exports and imports of goods, in absolute terms (Figure 1.12). Three countries, Singapore, India and Malaysia, are the largest merchandise exporters, accounting for half of total exports in 2019. India and Singapore are also the largest importers. This pattern has remained largely consistent over time.

Figure 1.12 Shares of large intra-Commonwealth merchandise traders, 2019

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTADstat dataset)

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTADstat dataset)

Among Commonwealth developed countries, the UK was the fifth-largest exporter and the third-largest importer while Canada was the seventh-largest exporter and the sixth-largest importer in 2019. This owes to the significant regional trade of these economies - namely, the UK with the EU and Canada with the USA and Mexico.

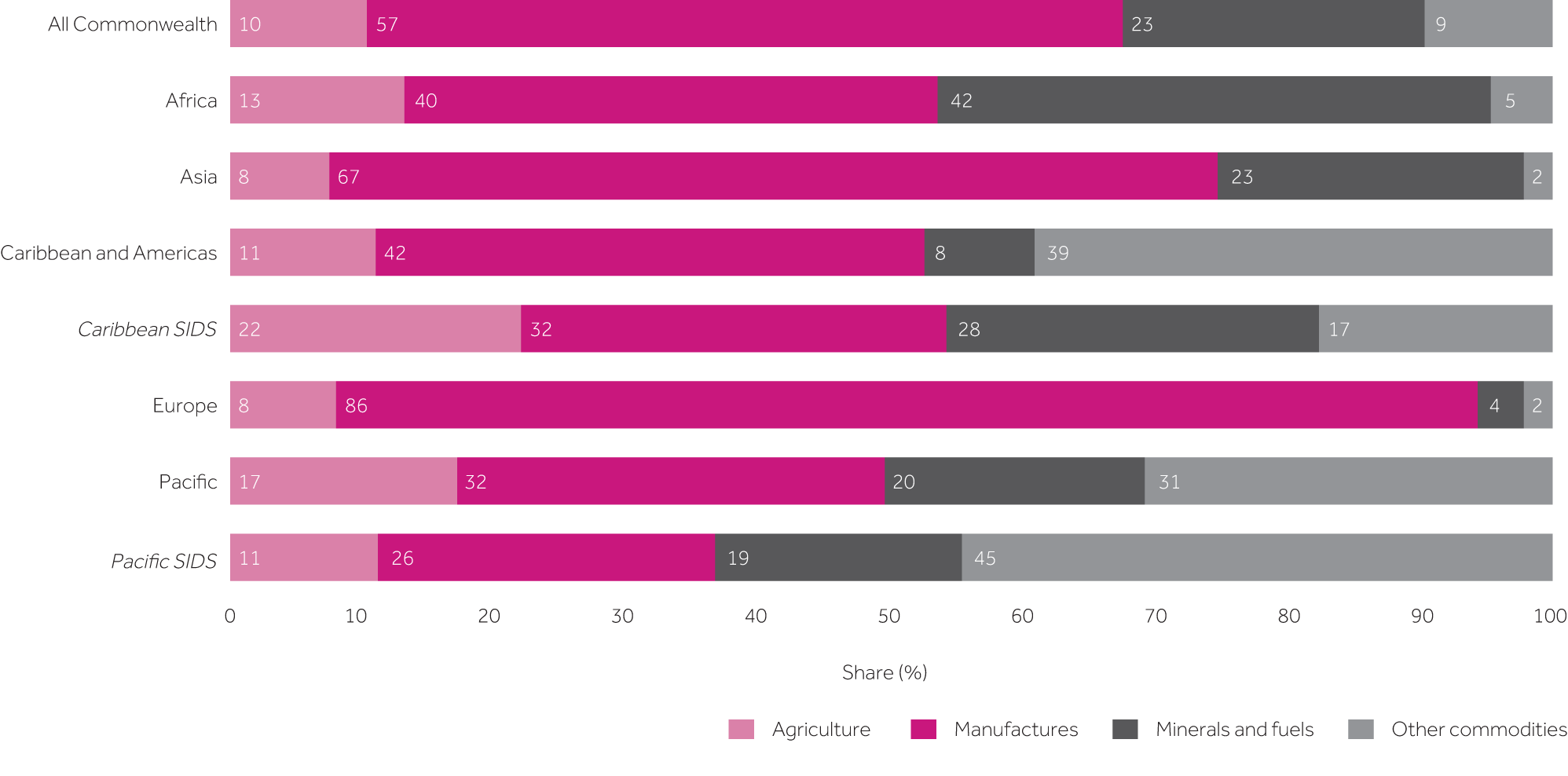

Two sectors contributed almost half of intra-Commonwealth merchandise exports: manufactured goods (US$250 billion, or almost 60 per cent) and commodities comprising minerals and fuels ($99.5 billion, or 23 per cent) (Figure 1.13). The preponderance of manufacturing in the overall goods exports of Commonwealth Europe (86 per cent) and Asia (67 per cent) suggests these countries were relatively more exposed to COVID-19-related demand and supply disruptions to this sector and trade. Commonwealth Africa, where non-manufactured goods comprise around 60 per cent of merchandise exports, was more vulnerable to volatility in commodity prices, which affected the revenues of several commodity-dependent countries (see Box 1.6).

Figure 1.13 Intra-Commonwealth merchandise exports by sector and region, 2019

Note: "Other commodities" includes gold and coins (non-monetary).

Note: "Other commodities" includes gold and coins (non-monetary).Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTADstat dataset)

Intra-Commonwealth services trade

Services trade is an important component of Commonwealth countries' exports, as noted earlier in this chapter. Intra-Commonwealth services exports are growing rapidly, having more than doubled from around US$98 billion in 2005 to $238 billion in 2019.

Developing countries are the leading services suppliers, accounting for around 60 per cent of intra-Commonwealth exports in 2019. Services exports by Asian countries, especially India, Singapore and Malaysia, have become more significant in recent years.

In 2019, Singapore was the largest intra-Commonwealth services exporter while India was the largest services importer (Figure 1.14). Almost all the developed countries are ranked in the top 10 intra-Commonwealth services traders. The UK is the second-largest exporter and the third-largest importer of services, followed by Australia, which is the fourth-largest importer and exporter. Of the African members, only South Africa and Nigeria rank among the top 10 services economies.

Figure 1.14 Country shares of intra-Commonwealth services exports and imports, 2019

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using OECD-BaTIS dataset)

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using OECD-BaTIS dataset)

In 2019, around 53 per cent of intra-Commonwealth services exports originated from Asia, followed by 22 per cent from the three European members. The share of the Pacific members, although relatively smaller, is higher than the combined share of African and Caribbean members (Figure 1.15).

Figure 1.15 Regional and sectoral distribution of intra-Commonwealth services exports, 2019

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (estimated using WTO-OECD BaTIS dataset)

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (estimated using WTO-OECD BaTIS dataset)

The sectoral composition of intra-Commonwealth services trade displays significant vulnerabilities to a shock like COVID-19. Travel is the largest category, accounting for almost 30 per cent of services exports - and this is larger than the corresponding global share (21 per cent), as discussed earlier. The share of transport services (16 per cent) and ICT services (13 per cent) combined is around 30 per cent. Although many services sectors, such as education, financial services and health, have adapted by delivering more online, communal services such as events and hospitality require in-person interaction.

The growth of intra-Commonwealth services exports has been marginally higher than the global growth rate for this sector. During 2005-2019, intra-Commonwealth services exports grew at around 6.88 per cent per annum while the growth rate of world services trade was around 6.38 per cent (Figure 1.16). The growth rate of intra-Commonwealth services exports in this period was also slightly higher than the same for Commonwealth countries' global exports (6.45 per cent). This is driven partly by the increase in exports of services by developing economies, especially Singapore and Malaysia, as well as the effect of the Commonwealth advantage in driving trade in services. This servicification trend is observed in both developed and developing countries (Box 1.2).

Figure 1.16 Growth rate of intra-Commonwealth services exports, 2005-2019 average

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (estimated using WTO-OECD BaTIS dataset)

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (estimated using WTO-OECD BaTIS dataset)

Box 1.2 Rising servicification trends in Commonwealth developing and developed countries

The process of servicification has two main components. On the one hand, changes in consumption patterns as a result of increasing per capita incomes tend to shift demand and therefore production towards services. At the same time, technological change means that more activities within industrial firms are in fact services. During 2005-2019, Commonwealth developed economies increased their share of intra-Commonwealth services exports as well as services imports. A similar trend is observed in developing members (Figure 1.17) but their services exports have grown at a much faster pace.

Figure 1.17 Servicification of intra-Commonwealth trade over time

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTADstat and OECD-WTO BaTIS dataset)

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTADstat and OECD-WTO BaTIS dataset)

1.4 COVID-19 implications for Commonwealth trade

COVID-19 has caused severe economic disruptions to the Commonwealth and globally. The global recession and GDP contraction in major trading partners (Box 1.3), together with various COVID-19-related disruptions, have dealt a strong blow to Commonwealth countries' exports. For 2020, the Commonwealth's global trade flows are estimated at US$3.55 trillion. This amounts to a drop of $145 billion from 2019.

Box 1.3 COVID-19 and economic contractions in the Commonwealth's largest export markets

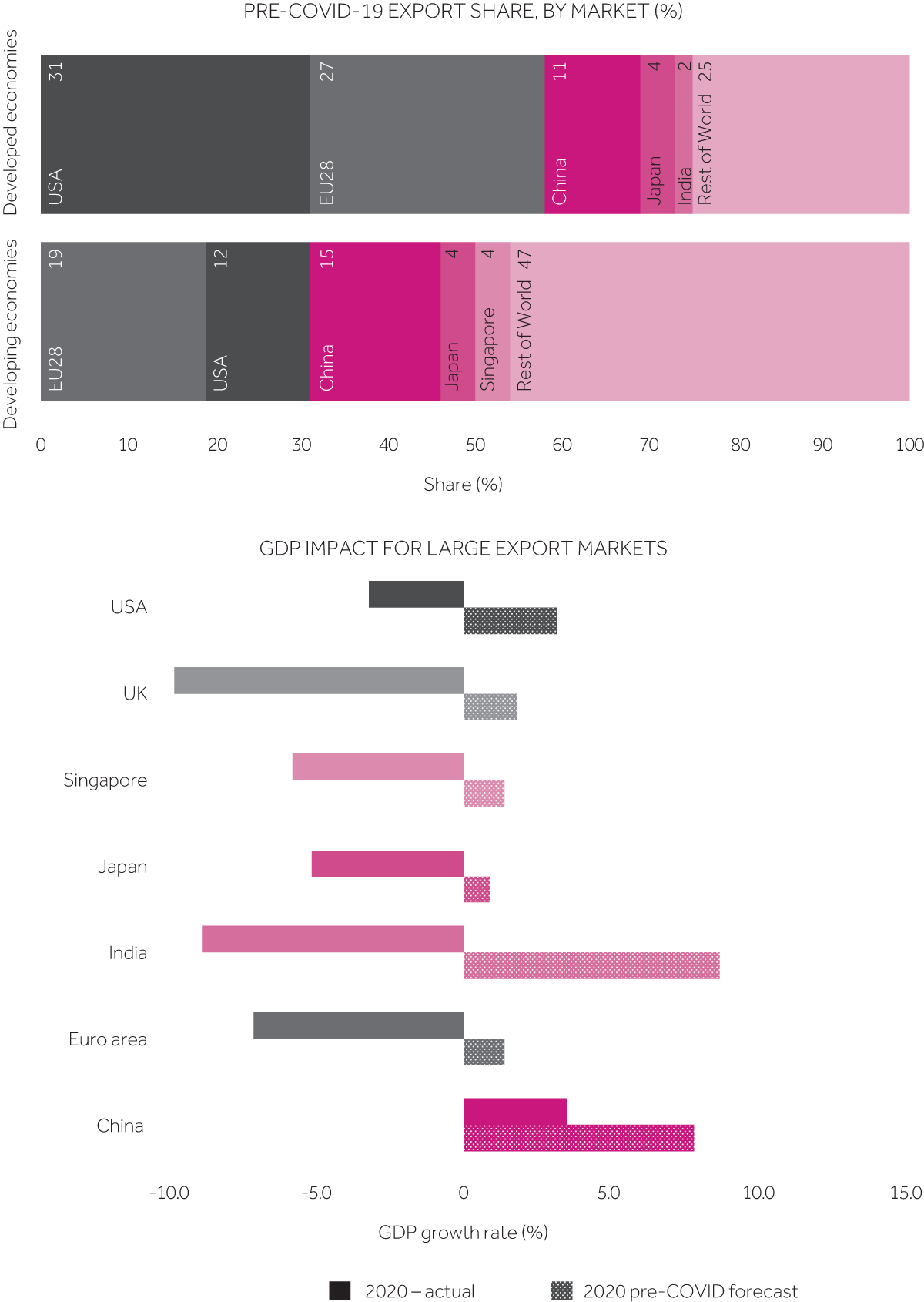

International trade is highly responsive to changes in market size. COVID-19 has constrained economic growth in the Commonwealth's major export markets, adversely affecting demand for goods and services (Figure 1.18). Apart from China, where GDP expanded by 2.3 per cent, the other major destinations for Commonwealth exports recorded significant contractions in GDP in 2020. In India and Singapore, GDP declined by more than 5 per cent. In the USA, which absorbs 31 per cent of developed members' goods and services exports and 12 per cent of those from developing members, GDP contracted by 3.5 per cent. The EU, which collectively represents the second-largest market for Commonwealth exports, contracted by 6.6 per cent. Within the EU-27, growth in the three top destinations for Commonwealth exports - Germany, France and the Netherlands - fell by 4.9 per cent, 8.2 per cent and 3.7 per cent, respectively. Similarly, the GDP of the UK, a key destination for intra-Commonwealth exports (see Chapter 5), contracted by around 9.9 per cent.

Figure 1.18 Commonwealth market share and GDP drop for large export markets (%)

Note: The left panel reflects combined share of goods and services. EU-28 includes the UK because it was an EU member until 31 January 2020. China and Hong Kong are aggregated in the left panel.

Note: The left panel reflects combined share of goods and services. EU-28 includes the UK because it was an EU member until 31 January 2020. China and Hong Kong are aggregated in the left panel.Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTADstat and WTO-OECD BaTIS datasets and data from the IMF and World Bank Outlook)

These markets collectively absorb around 75 per cent of Commonwealth developed members' exports and around half from developing countries. Most of these economies are still under varying degrees of lockdown. The protracted pandemic, coupled with an on-going deep recession, not only has adversely affected short-term export demand but also portends serious challenges for a quick trade recovery in both Commonwealth developed and developing countries in 2021. Aside from these direct implications for trade in goods and services, a reduction in growth in these major economies could have several indirect knock-on effects for Commonwealth developing members, including through reduced Aid for Trade and other official development assistance to LDCs and highly vulnerable small states.

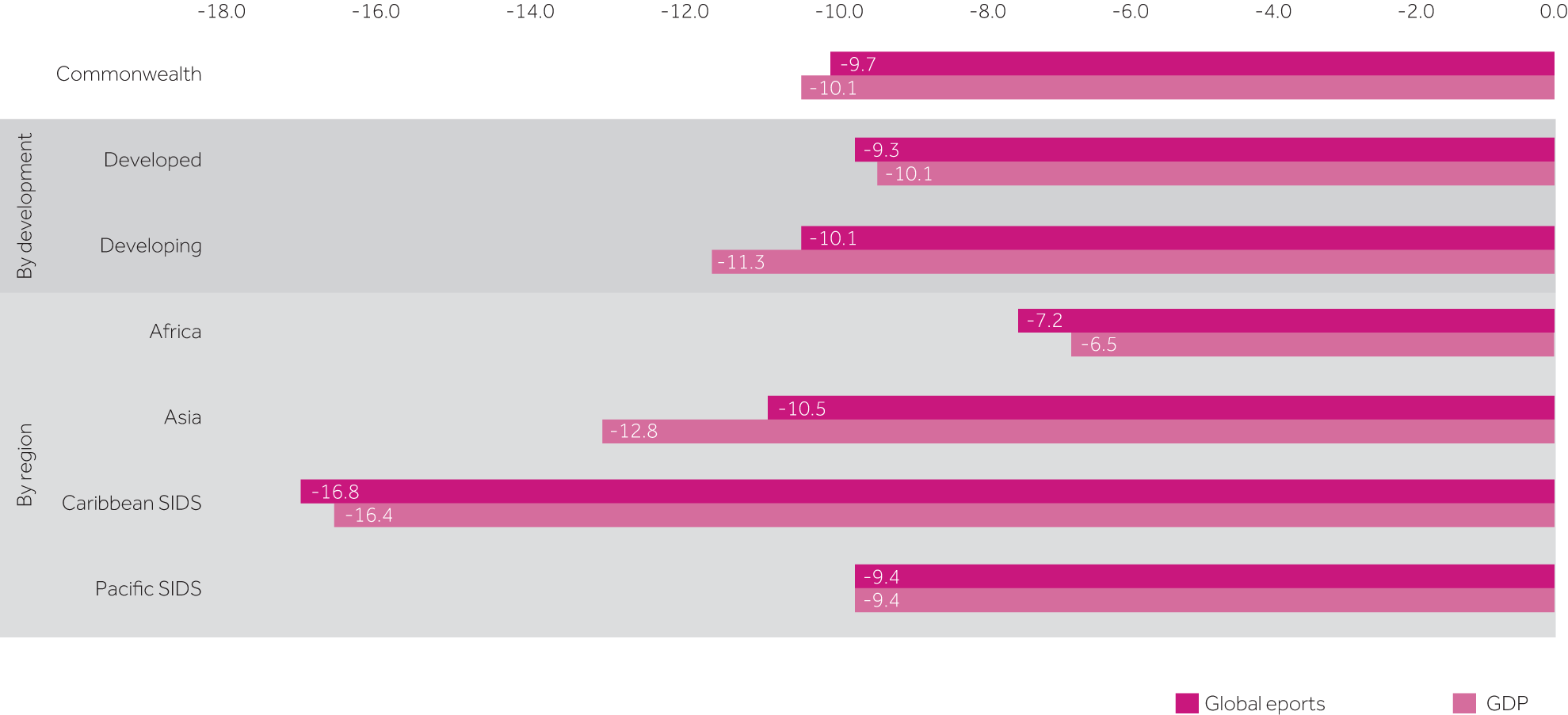

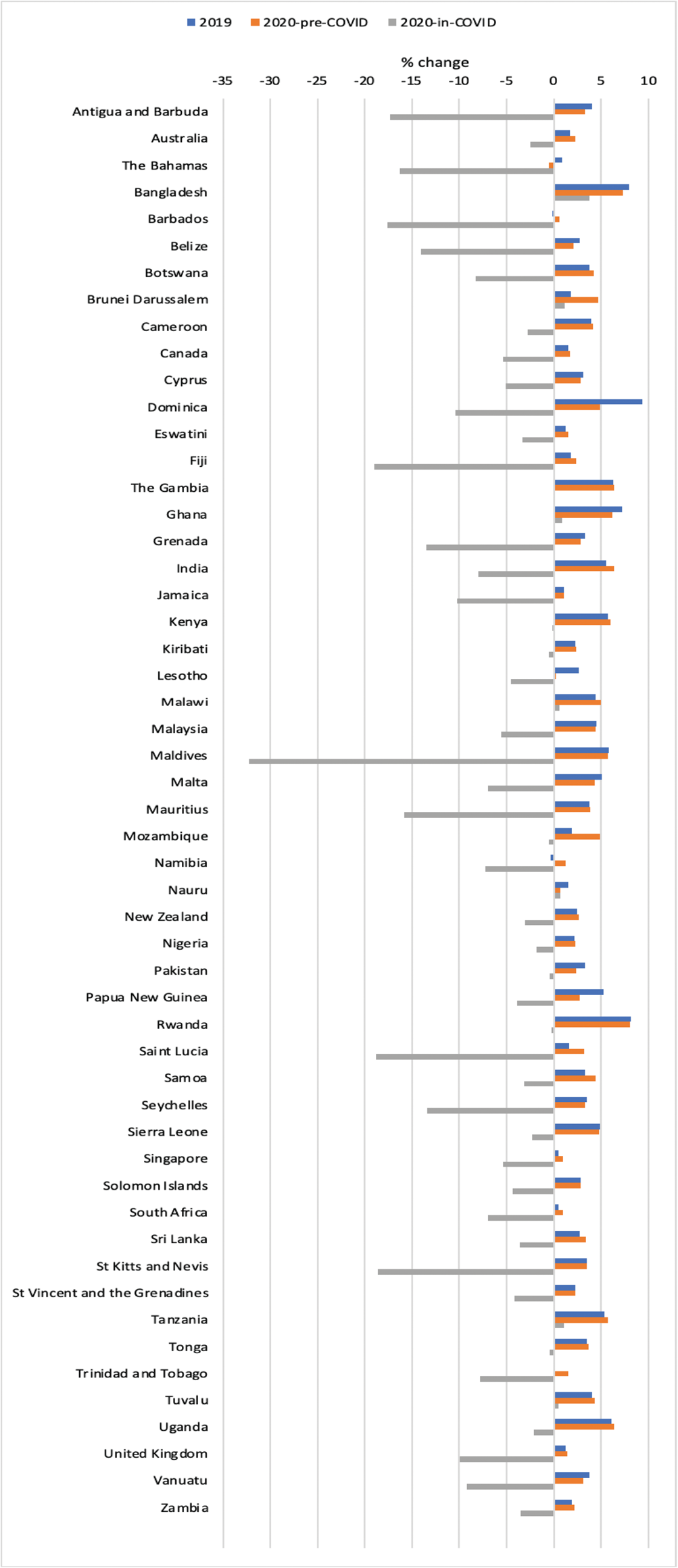

Relative to pre-pandemic growth trends, Commonwealth economies are estimated to contract by around 10 per cent in 2020 (Annex 1.2). This economic contraction has directly translated to a drop in trade flows (Figure 1.19), but with a varying effect across Commonwealth regions and development levels. Although global exports from all Commonwealth economies have declined, the drop is relatively higher for developing Commonwealth countries, whose exports have contracted by around 10.1 per cent. This could reflect, among others, limited economic support to the firms and businesses in these countries during the pandemic. Second, these countries largely rely on the export markets of advanced economies, which are still reeling from COVID-19. In absolute terms, Asian economies suffered the largest decline in exports (at US$146 billion), followed by African ($20 billion), Caribbean ($4.2 billion) and Pacific members (1.3 billion). However, in relative terms, the Caribbean SIDS underwent a greater slump. Their global exports shrank by almost 20 per cent. These SIDS largely rely on the exports of services, particularly travel and tourism, which were hit hard in this pandemic (see Chapter 5).

Figure 1.19 Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Commonwealth countries' global exports in 2020

Note: Calculated as the difference between pre-COVID (October 2019) and in-COVID (April 2021) estimates of the IMF. The GDP estimates are used to compute trade flows at country and regional levels.

Note: Calculated as the difference between pre-COVID (October 2019) and in-COVID (April 2021) estimates of the IMF. The GDP estimates are used to compute trade flows at country and regional levels.Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTADstat and WDI datasets and IMF and World Bank data)

Intra-Commonwealth trade flows are estimated at around US$641 billion in 2020. Compared with the pre-pandemic projection ($701 billion), this suggests an export loss of $60 billion in a single year. The pandemic has affected the intra-Commonwealth exports of all regions (Table 1.4). However, in absolute terms, Asian economies have suffered the biggest decline in exports (at $36 billion), followed by African ($6.5 billion), Caribbean ($ 4.2 billion) and Pacific members ($5 billion). Among these groupings, the Caribbean SIDS are the most affected in relative terms, with their intra-Commonwealth exports shrinking by almost 16 per cent in 2020. All leading intra-Commonwealth exporters have been affected (Figure 1.20).

Figure 1.20 COVID-19 shock and intra-Commonwealth trade flows in goods and services, 2019 vs. 2020

Note: Calculated as the difference between pre-COVID (October 2019) and in-COVID (April 2021) estimates of the IMF. The GDP estimates are used to compute trade flows at country and regional levels.

Note: Calculated as the difference between pre-COVID (October 2019) and in-COVID (April 2021) estimates of the IMF. The GDP estimates are used to compute trade flows at country and regional levels.Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTADstat and WDI datasets and IMF and World Bank data)

Table 1.4 Regional variation in COVID-19 impact on intra-Commonwealth trade (US$ million), 2019 vs. 2020

| 2019 | 2020 (Pre- and in-COVID) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Forecast | Actual | ||

| Commonwealth | 672,647 | 701,248 | 641,316 |

| By development | |||

| Developed | 218,613 | 234,420 | 216,220 |

| Developing | 454,034 | 466,737 | 425,096 |

| By region | |||

| Africa | 89,354 | 99,395 | 92,797 |

| Asia | 352,452 | 357,915 | 321,330 |

| Caribbean and Americas | 44,831 | 50,746 | 46,594 |

| Caribbean SIDS | 6,296 | 6,715 | 5,662 |

| Europe | 90,468 | 96,644 | 86,017 |

| Pacific | 95,541 | 99,548 | 94,577 |

| Pacific SIDS | 5,931 | 5,803 | 5,306 |

Note: Calculated as the difference between pre-COVID (October 2019) and in-COVID (January 2020) estimates of the IMF and World Bank. The GDP estimates for 2020 are used to compute trade flows at country and regional levels

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTADstat and WDI datasets and IMF and World Bank data)

1.4.1 COVID-19 and goods trade

With two-thirds of the Commonwealth's global and intra-Commonwealth trade being in manufactured goods and commodities, many member countries, especially developing countries, have been hit hard by the real economy consequences of COVID-19.

The pandemic has adversely affected the global and intra-Commonwealth merchandise exports of member countries since early January 2020, immediately after the outbreak of the coronavirus in China in December 2019. However, the greatest effect occurred during April and May 2020, when many large export markets in Europe and the USA imposed lockdowns. In these two months, exports of Commonwealth members dropped to almost half compared with the baseline (Figure 1.21). The impact was relatively higher for intra-Commonwealth exports compared with global exports as many of the large intra-Commonwealth traders - including India, Singapore, South Africa and the UK - experienced an economic contraction, affecting the supply and demand of their merchandise (see Box 1.4). Exports plateaued in May 2020 but rebounded in June 2020 as firms sought to adapt to the containment measures. Merchandise exports are gradually recovering as lockdowns and restrictions on economic activities are lifted in many countries. However, in December 2020, the Commonwealth's exports were still well below the pre-pandemic level in December 2019.

Figure 1.21 Impact of the pandemic on Commonwealth merchandise exports, December 2019 to December 2020

Note: Exports are indexed to 1 in December 2019. As a result of data reporting delays in LDCs and small states, the chart contains information for only 25 Commonwealth countries.

Note: Exports are indexed to 1 in December 2019. As a result of data reporting delays in LDCs and small states, the chart contains information for only 25 Commonwealth countries.Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using ITC data)

The drop in Commonwealth countries' exports has strong linkages with the incidence of the virus (see Box 1.4). Countries with high numbers of infections (and deaths) and with strict lockdowns have also experienced a large decline in trade flows.

Box 1.4 Linkages between COVID-19 infections and merchandise exports in the Commonwealth

In a study for the Commonwealth Secretariat, Khorana and Martínez-Zarzoso (2021) estimate a gravity model on monthly trade flow data to explore the effect of incidence of COVID-19 on Commonwealth members' global and intra-Commonwealth merchandise exports. The results provide strong evidence of a correlation between the Commonwealth's exports and the number of infections, deaths and stringency of lockdowns9 in source and destination markets. A 10 per cent increase in the number of COVID-19 infections in the exporting country decreases exports by 0.33 per cent. The corresponding effect for the number of deaths is slightly lower (0.028 per cent) but that for the stringency index is higher, at about 0.4 per cent. The drop reflects interruptions in production and exporting activities in the short term at the onset of the pandemic (Table 1.5).

The estimated trade decline for five Commonwealth countries - Canada, India, Pakistan, South Africa and the UK - is very high (above 10 per cent). These five economies account for around 60 per cent of the Commonwealth's global exports and 40 per cent of intra-Commonwealth exports. The relatively high incidence of COVID-19 in these countries, in terms of numbers of infections and deaths, directly explains a larger decline in the Commonwealth's trade flows. By contrast, the Pacific SIDS have largely been shielded from the health effects of COVID-19. Moreover, these economies have relatively lesser proportions of merchandise in their exports, which is reflected in a relatively small drop in their goods trade (less than 5 per cent).

These regression results are robust to alternative estimation approaches (Pseudo Poisson Maximum Likelihood, PPML, and Ordinary Least Squares, OLS), using monthly lagged data (to account for simultaneity bias), and to the inclusion of a rigorous set of exporter and importer fixed effects to account for omitted variables and multilateral resistance. They also hold when the gravity variables - namely, distance, free trade agreement (FTA), common language and common border - are replaced by bilateral fixed effects. The projections of trade trends in the short term present a negative change in exports for all countries, raising the need for policy interventions and support to increase the resilience of supply chains.

Table 1.5 Modelling results: COVID-19 effect on Commonwealth countries' merchandise exports (% decrease)

| % decrease in exports | Commonwealth members | Share of CW trade | Share of Intra-CW trade |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10+ | Canada, India, Pakistan, South Africa, United Kingdom | 56.91 | 40.83 |

| 7-10 | Australia, Bangladesh, Cameroon, Ghana, Jamaica, Kenya, Nigeria, Singapore, Zambia | 29.87 | 38.44 |

| 5-7 | The Bahamas, Belize, Botswana, Cyprus, Eswatini, The Gambia, Guyana, Malawi, Malaysia, Malta, Mozambique, Namibia, New Zealand, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Sri Lanka, Trinidad and Tobago, Uganda | 11.87 | 18.37 |

| 0-5 | Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Brunei Darussalem, Dominica, Fiji, Kiribati, Lesotho, Mauritius, Nauru, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Seychelles, Tanzania, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu | 1.16 | 2.12 |

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using data from UNCTADstat dataset and estimates from Khorana and Martínez-Zarzoso (2021))

COVID-19 has impacted goods trade through both supply and demand shocks. Quarantines, lockdowns, social distancing and high levels of uncertainty have led to a significant drop in demand for goods and services, with GVCs transmitting the economic shock to upstream supplier countries (Escaith and Khorana, 2021). For example, reduced consumer demand and supply shocks have hit garment manufacturers and workers in the Commonwealth, especially in Bangladesh and Lesotho (Box 1.5).

Box 1.5 COVID-19 hits garments manufacturing in the Commonwealth

Global garment supply chains are highly integrated, making them extremely susceptible to the disruptions to trade and the movement of goods and persons caused by COVID-19. In the early stages of the pandemic, lockdowns in China resulted in severe delays to Chinese exports of raw materials (including fabric), with significant impacts on production for garment manufacturers in Bangladesh and other garment-producing Commonwealth countries that rely heavily on imported inputs. Across the Asia-Pacific region, garment manufactures have faced disruptions to up to 60 per cent of their supplies of imported inputs (ILO, 2020).

Lockdowns and mandatory closures of clothing retail stores in Europe, the USA and the world led to a sharp fall in consumer demand. This had a severe impact on garment manufacturing industries in Bangladesh, Lesotho and other Commonwealth countries that supply large quantities of garments to these markets. In the first half of 2020, garment-producing countries across Asia saw their exports to major buying countries fall by up to 70 per cent (ILO, 2020).

Some suppliers were hit with large-scale cancellation or postponement of production orders, often retrospectively in cases where orders were already in process or on the verge of completion.10 Many manufacturers also suffered delays to payments for completed orders, with buyers invoking "force majeure" clauses in their contracts. The direct health effects of COVID-19 have also impacted the availability of workers, dealing a further blow to production capacity in garment-producing Commonwealth countries.

The adverse impacts on the industry have major implications for garment sector workers, particularly women, who comprise most factory workers in key Commonwealth garment manufacturing countries (including Bangladesh, India, Lesotho, Pakistan and Sri Lanka). Many workers were already paid low wages and had poor job security and weak social safety nets even before the pandemic, and these vulnerabilities have been exacerbated.11 In addition, incomes decreased among many workers who had retained their jobs, falling by 21 per cent, on average, between March and August 2020 compared with pre-pandemic levels (Worker Rights Consortium, 2020).

If these production constraints persist, there is a risk that clothing brands may shift their manufacturing away from some Commonwealth members in favour of other sourcing locations to mitigate supply chain risks (Teodoro and Rodriquez, 2020). This would feed into the wider structural shifts already underway in export-oriented apparel manufacturing GVCs, resulting in shorter value chains (see Chapter 3). As countries continue to battle to contain the spread of COVID-19, a wider garment sector recovery may be some way off, with a lag before garment production and demand for apparel returns to pre-pandemic levels. In the meantime, further support for garment manufacturers and workers will be necessary.

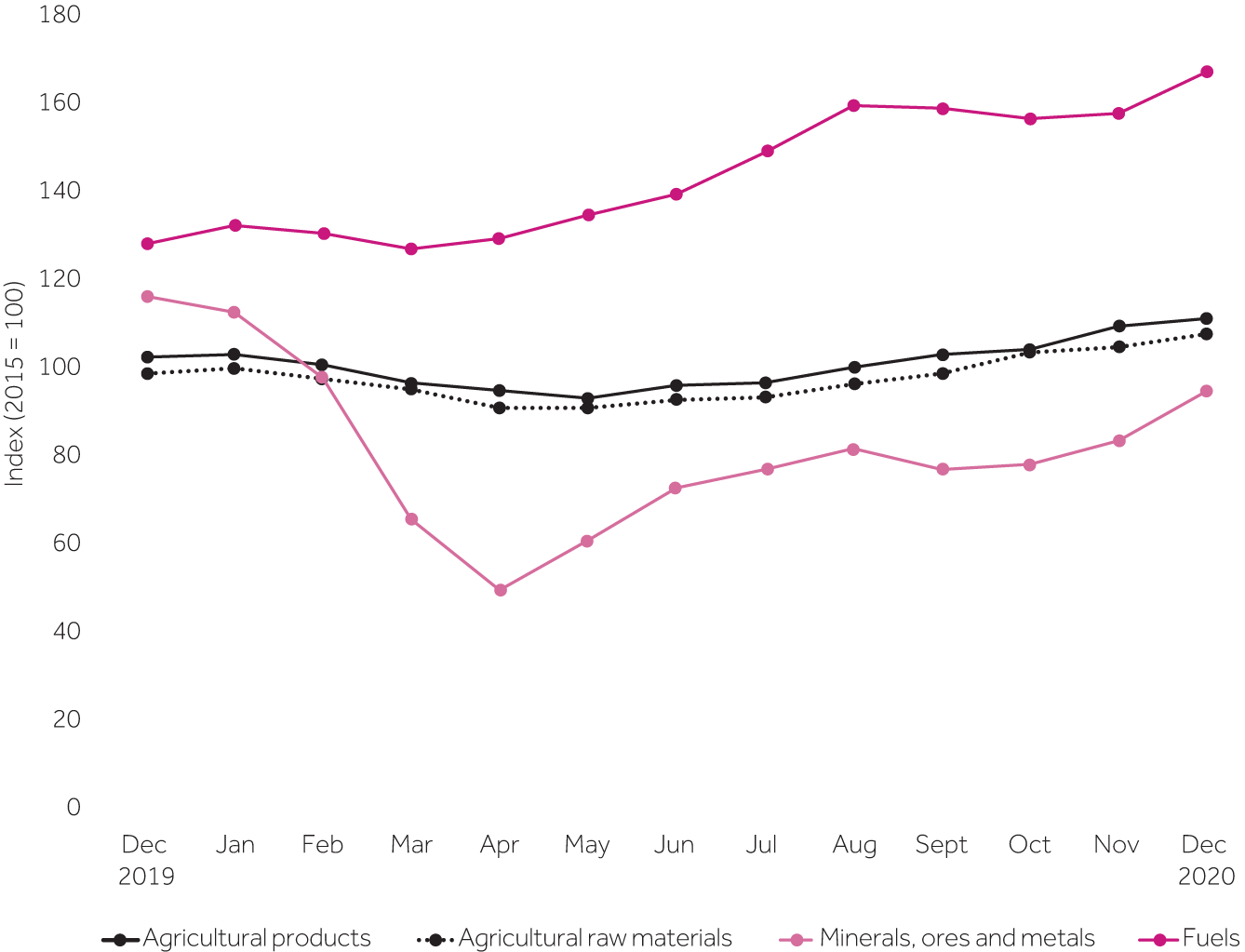

Commodities constitute around one-third of world merchandise exports and approximately 20 per cent of these exports originate from Commonwealth countries. Commodities are also a key component of the Commonwealth's overall merchandise exports, accounting for 45 per cent of these exports (higher than the world average of 33 per cent). Many developed and developing Commonwealth countries are heavily dependent on commodities exports - 31 members derive more than 80 per cent of their merchandise export earnings from primary commodities. The shares of commodities in the exports of New Zealand and Australia are above 70 per cent; they are even higher for the Pacific SIDS (97 per cent) and SSA countries (79 per cent). COVID-related restrictions have led to a sharp decline in commodity prices, adversely affecting the exports of many developed and developing countries (Box 1.6).

Box 1.6 Commodities exports and COVID-19

Commonwealth countries' main commodity exports are food products, mineral ores, metals and fuels. Among these, fuels are the largest exported item, constituting around 42 per cent of all commodities exports. This is followed by mineral ores (36 per cent) and agri-food products (22 per cent).

Around 55 per cent of these exports are destined for five markets: China, the USA, the EU-27, the UK and Australia. The COVID-19 pandemic has negatively affected demand for commodities in these key markets, leading to a collapse in commodity prices, particularly for fuels. Prices of other key commodities, such as agricultural products and mineral ores, have been relatively less affected. Nevertheless, the reduction in demand, along with challenges associated with production and exporting, led to an aggregate export loss of around US$125 billion for Commonwealth countries in 2020. This represents a decline of 24 per cent compared with the pre-pandemic trend. The Commonwealth's commodity exports to the USA were hit the hardest (falling by $50 billion) followed by those to the EU-27 ($41 billion) and China ($26 billion); notably, in a diplomatic dispute since Canberra's call for an international investigation into the origins of COVID-19, Australian imports have encountered difficulties entering the Chinese market, including timber, barley, beef and some types of coal (see Chapter 4). Exports to the UK were $400 million below the estimate for a "business-as-usual" situation.

In value terms, Commonwealth developed countries experienced a large drop in commodities exports, amounting to US$57 billion, driven mainly by a fall in exports from Australia (see above) and Canada. In absolute terms, Asian Commonwealth members were the second most affected group, closely followed by African members. However, in relative terms, Caribbean members were hit more severely. Their commodities exports dropped by 60 per cent compared with the historical average. This owed mainly to sharp declines in exports of crude and refined oil as well as of natural gases from Trinidad and Tobago and, to a lesser extent, exports of sugar and crustaceans from Belize, mainly to the EU-27. Overall, the Pacific region was the least affected.

The prices of most commodities surged in the second half of 2020, offsetting some of the trade losses in commodity-dependent economies (Figure 1.22). Resumption of transport activities is pushing up oil prices, which traded at US$66 per barrel in the first week of March 2021. Similarly, the on-going transition towards electric and hybrid vehicles is incentivising demand for minerals used to manufacture batteries and chips. There is the possibility of a new commodity super cycle, which could support a relatively fast recovery in commodities trade for Commonwealth countries (The Economist, 2021a).

Figure 1.22 Monthly variation in commodity price indices in 2020

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calulated using data from UNCTADstat dataset)

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calulated using data from UNCTADstat dataset)

1.4.2 COVID-19 and services trade

Services account for at least half of total economic activity in terms of GDP in Commonwealth members. Levels are particularly high in high-income countries but also in some SIDS, where activities like tourism and finance - both services - are important in the overall economy (Shepherd and Shingal, 2021). The pandemic has had significant impacts on the services sector. While all Commonwealth countries have been subject to shocks related to COVID-19, extents and recovery paths have varied substantially (Box 1.7).

Box 1.7 Drop in services exports during the COVID-19 pandemic

Analysis of monthly services exports for eight Commonwealth countries from January to December 2020 provides some indication of the immediate and direct effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on services trade. Most countries reporting high frequency data have seen major reductions to services exports starting from January 2020 when compared with the corresponding months during 2019. The extent of the decline is striking. Services exports from Tanzania and Uganda have collapsed by over 60 per cent while those of Australia and Kenya have dipped by around 40 per cent (see Figure 1.23).

COVID-19 impact on services exports of selected Commonwealth countries, 2020 vs. 2019

Note: The chart presents percentage change in exports in 2020 compared with the corresponding month in 2019 for selected Commonwealth countries that report monthly services export data to the WTO.

Note: The chart presents percentage change in exports in 2020 compared with the corresponding month in 2019 for selected Commonwealth countries that report monthly services export data to the WTO.Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using data from the WTO)

These economic shocks are massive, and the pace of recovery varies by country. The services exports of India and Malta have rebounded to a great extent, but those of Uganda in December 2020 were almost half the level recorded in December 2019. Similarly, Australia's services exports were about 60 per cent of December 2019 levels, while those of the UK were about three-quarters of the levels observed in the corresponding months of 2019. Whereas services exported by Uganda and Tanzania have declined significantly and have not yet recovered, by September 2020 Pakistan's services exports had already rebounded to December 2019 levels (despite falling by 20 per cent in April 2020).

There is no clear pattern according to development level, although sectoral specialisations have influenced the nature of impacts. Economies that are highly dependent on services trade that requires in-person interactions, such as tourism, have seen steep and sustained declines in their exports (Kenya, Uganda), while those exporting ICT-related services have performed better (India, Pakistan). The services exports of Caribbean countries, as well as those of the Pacific islands, which largely rely on travel and tourism-related services, were down by around 70 per cent in 2020 (WTO, 2020a).12

COVID-19 and substituting modes of supply

Services exports contribute 35 per cent of intra-Commonwealth trade, which is significantly higher than the share of services in world trade (25 per cent). Commonwealth members with large tourism and travel sectors, especially the 25 SIDS, have been hard hit, as the global tourist economy has contracted substantially.

This has adversely affected women workers (Box 1.8). As employment for women increases globally, there has also been a corresponding shift into service sectors. An estimated 43 per cent of women across the Commonwealth were employed in the services sector in 2019, up from 30 per cent in 2000. In developed countries, over 90 per cent of women work in the services sector, an increase of 5 percentage points from 2000. In developing countries, 36 per cent of employed women work in services sectors, an increase of 16 percentage points since 2000. New trends in global trade, particularly the rise in services, GVCs and the digital economy, now offer more economic opportunities to women.

Transport and travel constitute around half of intra-Commonwealth services exports. Air travel has been significantly affected by border closures and international travel restrictions. The International Air Transport Association has projected US$126 billion in losses for 2020, marking the worst annual financial result in aviation history, with smaller losses of $47.7 billion in 2021 (IATA, 2021). Airlines of several Commonwealth countries, including Antigua and Barbuda, Australia, Canada, India, Namibia, South Africa and the UK, have entered bankruptcy protection/administration or been liquidated since the start of the pandemic. Some of the bigger airlines are expected to survive following restructurings and a rebound in demand. Aside from the direct effects on intra-Commonwealth travel and tourism-related services exports, the collapse in global aviation also impacted some goods trade, especially passenger-based air freight services that deliver high value exports (e.g. East African horticulture and floriculture direct to the UK).

Box 1.8 Entrepreneurship, trade and women's economic empowerment

Across the Commonwealth, women make up approximately 50 per cent of the population and 30 per cent of the labour force. However, compared with men, women contribute less to global GDP and significantly less to international trade. Despite 122 World Trade Organization (WTO) members and observers, including 31 Commonwealth countries, endorsing the 2017 Joint Declaration on Trade and Women's Economic Empowerment, women remain under-represented in trade. In one estimate, only 15 per cent of exporting firms are led by women (ITC, 2015). Factors such as a higher share of unpaid or underpaid work at home and in the informal sector, as well as barriers to entry for entrepreneurship and trade, limit women's participation.

Women-owned businesses have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic. This is because they are over-represented in high-risk sectors such as tourism, transport and travel, retail, food services, accommodation, entertainment and recreation, and manufacturing across economies of all income categories. Despite the pandemic's adverse impact, some women business owners are adjusting to the new reality. According to the 2020 Mastercard Index of Women in Entrepreneurship Report, 42 per cent of women-owned businesses have shifted to a digital business model, 37 per cent are developing an area of business to meet local or global needs and 34 per cent have identified new business opportunities since the pandemic.

As employment for women increases globally, there has also been a corresponding shift into service sectors. An estimated 43 per cent of women across the Commonwealth were employed in the services sector in 2019, up from 30 per cent in 2000. In developed countries, over 90 per cent of women work in the services sector, an increase of 5 percentage points from 2000. In developing countries, 36 per cent of employed women work in services sectors, an increase of 16 percentage points since 2000. New trends in global trade, particularly the rise in services, GVCs and the digital economy, now offer more economic opportunities to women.

However, fewer women are engaged in tradeable services than men. For Commonwealth countries, on average, 5 per cent of women are engaged in tradeable service sectors compared with 18 per cent of men (calculated as the share of total employment). This varies across regions, with women in developed countries engaged in an estimated 16 per cent of tradeable services, followed by Caribbean SIDS with 15 per cent. Asian countries fall short with less than 30 per cent of women represented in overall employment, less than 5 per cent of whom are engaged in tradeable services.

Women face various challenges in taking advantage of the new opportunities for greater inclusion and empowerment. For example, they face greater non-tariff measures such as access to financing to facilitate their participation in trade. For example, female-led formal SMEs face a credit gap of roughly US$300 billion (Gonzalez, 2017). They also face cultural barriers as well as time and skills constraints.

Given these challenges, there is a need for greater effort to advance women's participation in tradeable services and other areas of international trade. Policy-makers must strive to reduce trade barriers, promote and support women-led businesses and give equal opportunities for them to access credit and trade finance. In addition to mainstreaming gender issues in trade agreements, greater consideration should be given to fully implementing the Trade Facilitation Agreement, training women to access market opportunities and connecting women to these opportunities. The International Trade Centre (ITC) SheTrades initiative, supported by the Commonwealth Secretariat, can be used to provide training for women entrepreneurs and women-owned businesses to increase their competitiveness and participation in trade. The initiative aims to connect 3 million women to market by 2021 and has so far been utilised by four Commonwealth countries, Bangladesh, Kenya, Ghana and Nigeria, under its Commonwealth chapter.

The pandemic has affected how services are traded, with some suppliers increasingly using digital means to deliver across borders, as discussed in the next chapter. Generally, there are four modes of supply for services trade, as recognised by the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) of the World Trade Organization (WTO). They are:

- Mode 1 - cross-border supply using postal services or ICT; this includes digitally deliverable services (DDS), as discussed in Chapter 2

- Mode 2 - consumption abroad by consumers

- Mode 3 - commercial presence through branches or subsidiaries abroad

- Mode 4 - temporary movement of persons to deliver a service in another country

Modes 2 and 4, which directly involve movement of persons, account for around 14 per cent of the value of Commonwealth exports. The largest aggregate, however, is Mode 3 sales by foreign affiliates. Finally, Mode 1 accounts for 35 per cent of the value of Commonwealth services exports (Figure 1.24). While there is substantial evidence of a shift towards increased Mode 1 trade, including DDS, through online interactions, the ability to trade in this way is dependent on infrastructure, technological capacity, human capital and connectivity (Shepherd and Shingal, 2021). This is not always an option for service providers in many developing countries and LDCs, as discussed in Chapters 2 and 5.

Potential COVID-19 pandemic effects on services trade

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using WTO TiSMoS dataset for 2017)

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using WTO TiSMoS dataset for 2017)

The shocks of the pandemic have clear implications for the Commonwealth's services trade via Modes 2 and 4. In the case of Mode 2, it is consumers whose movements are impeded, with a corresponding reduction in trade, including exports of tourism, health and education services (Box 1.9). For Mode 4 it is service suppliers, again with a consequent reduction in trade. The case of Mode 3 is more ambiguous. The investment transactions at the base of Mode 3 can, in principle, take place without in-person interactions, although they have traditionally been an important part of large-scale investment decisions. To the extent that in-person interactions have become less desirable or less feasible, one effect may be to reduce the sales of foreign-owned firms in sectors where such interactions are important.13

Given the unprecedented scale and scope of the pandemic, it seems highly likely that trade has been reduced for Modes 2 and 4 but also potentially for Mode 3 (Shepherd and Shingal, 2021). However, the case of Mode 1 is quite different. This involves trade in services taking place through online means, subject to having access to the necessary infrastructure and services. As such, in some sectors, there is a countervailing force in the direction of increased services trade in Mode 1 specifically, as substitution across modes takes place in response to the pandemic (ibid).

Box 1.9 Switching modes? COVID-19 and the education services exports of Australia and Canada

The international education sector is important for Australia and Canada, and their universities draw students from around the world. In particular, Australia draws students from countries in East and Southeast Asia and Canada from Commonwealth partners, especially India.

Education services are Australia's third-largest export (AU$18.8 billion in 2014/15) and indirectly support 1.3 per cent of the country's total employment. In Canada, the sector accounts for just over 1.2 per cent of total services exports, which reflects Canada's relatively diversified economy. In both countries, especially Australia, Mode 2 accounts almost entirely for the delivery of education services. When the pandemic hit, Australia and Canada adopted extensive travel restrictions, with obvious implications for foreign students seeking entry for study purposes. Given the difficulty of safely ensuring in-person interactions, both countries transitioned to online learning for students inside the country - and via Mode 1 trade for those outside.

A notable difference between the two countries relates to the way in which travel restrictions have affected international students. In Australia, inward movements of non-Australian citizens were reduced to close to zero, with no special exemption for students. Once the extent of the disruption to the sector was clearer, including the possibility of halving the foreign student population, the federal government made changes to student visa rules to facilitate post-study work for students already in Australia, as well as rapidly allowing entry by new and returning students outside the country.

Canada, by contrast, continued to allow entry to registered students provided that their institution had an approved COVID-19 readiness plan. Partly because of this approach, industry estimates suggest that Canada's universities may see only a modest decline in revenue owing to the pandemic.

In both cases, there is an on-going question as to the level of future international student arrivals, assuming that travel restrictions are eased further. Another open question is whether the sector will transition durably to greater use of online platforms, which could potentially see some shift from a nearly exclusive reliance on Mode 2 trade to increased reliance on Mode 1 trade, especially as consumer and travel preferences change. There is no concrete indication yet that such a shift is taking place in more than a temporary way because of pandemic-related travel restrictions.

Source: Shepherd and Shingal (2021) for Commonwealth Secretariat1.5 Trade performance of LDCs, IPOA and COVID-19

The global recession has severely damaged the already fragile economies of LDCs by drastically reducing external demand for their goods and services, lowering prices of key exports and constraining inflows of investment and other resources. These economies generally lack the resilience to withstand these multiple economic shocks, owing to their limited productive capabilities and lack of diversification. Consequently, the fallout from the pandemic threatens to stall, or even reverse, developmental progress made by Commonwealth LDCs and may undermine their prospects for graduating out of the LDC category (see Chapter 5).

While the pandemic has set back the trade and development prospects of LDCs, they were already off track from the target to double their share of world exports by 2020, as envisaged by the Istanbul Programme of Action (IPOA) for LDCs for 2011-2020 and adopted through the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (see Chapter 5). This implied increasing the LDC share of global exports to 2 per cent, from one per cent at the start of IPOA implementation.

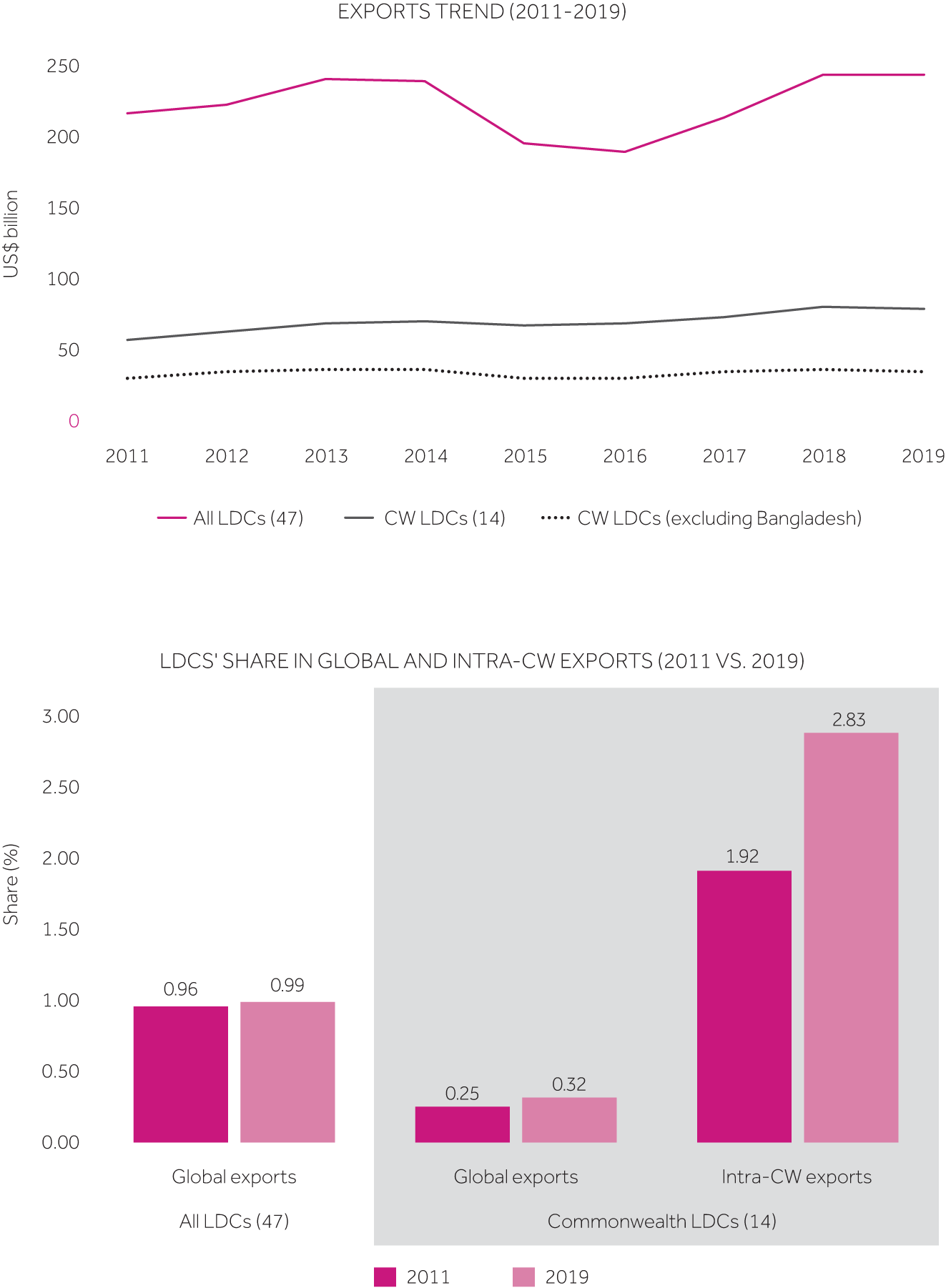

LDCs' global exports of goods and services rose from US$215 billion in 2011 to just over $243 billion in 2019. The exports of the 14 Commonwealth LDCs expanded from $56 billion to $79 billion (Annex 1.5). Despite some significant export growth in absolute terms over this period, the share of all LDCs in world merchandise trade stagnated just below 1 per cent, in both 2011 and 2019, although the dollar value of their exports in 2019 was the highest since 2000, at just over $243 billion. External shocks, including structural and cyclical factors and natural disasters in the Pacific and Southern Africa regions, also contributed to missing the target.

The trade performance of Commonwealth LDCs during this period was more robust than that of the other LDCs, with their exports growing from US$22 billion in 2005 to around $79 billion in 2019, almost fourfold. This reflects the significant contribution of intra-Commonwealth trade for many LDCs, especially in Asia and Africa. The share of Commonwealth LDCs in intra-Commonwealth trade in 2011 was 1.92 per cent - almost twice the corresponding share of all LDCs in world trade (Figure 1.25). During 2011-2019, the share of all LDCs in world trade stagnated, whereas that of the Commonwealth LDCs in intra-Commonwealth trade increased to 2.83 per cent over this period. Similarly, the share of Commonwealth LDCs in global trade also increased, from 0.25 per cent in 2011 to 0.32 per cent in 2019. A substantial portion of this increase is attributed to the export performance of Bangladesh, whose global exports almost doubled from $26 billion in 2011 to above $45 billion 2019.

Figure 1.25 Trade performance of LDCs during Istanbul Programme of Action

Note: The chart compares all LDCs' export share in world trade and 14 Commonwealth LDCs' share in world and intra-Commonwealth trade (goods and services combined) in 2011 and 2019.

Note: The chart compares all LDCs' export share in world trade and 14 Commonwealth LDCs' share in world and intra-Commonwealth trade (goods and services combined) in 2011 and 2019.Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTADstat and OECD-WTO BaTIS datasets)

A protracted pandemic poses a significant risk to sustainable graduation pathways for LDCs. Twelve LDCs are expected to graduate within the next four years. Vanuatu graduated in December 2020 and two more Commonwealth LDCs - Solomon Islands and Bangladesh - are set to follow in 2024 and 2026, respectively.

1.6 Commonwealth trade prospects towards 2022